This post is part of the Collective Punishment Basics series—a foundational guide for understanding how collective punishment shows up in schools and why it causes deep harm to disabled, neurodivergent, and vulnerable children. If you’re just starting to name what feels wrong, this is a place to begin.

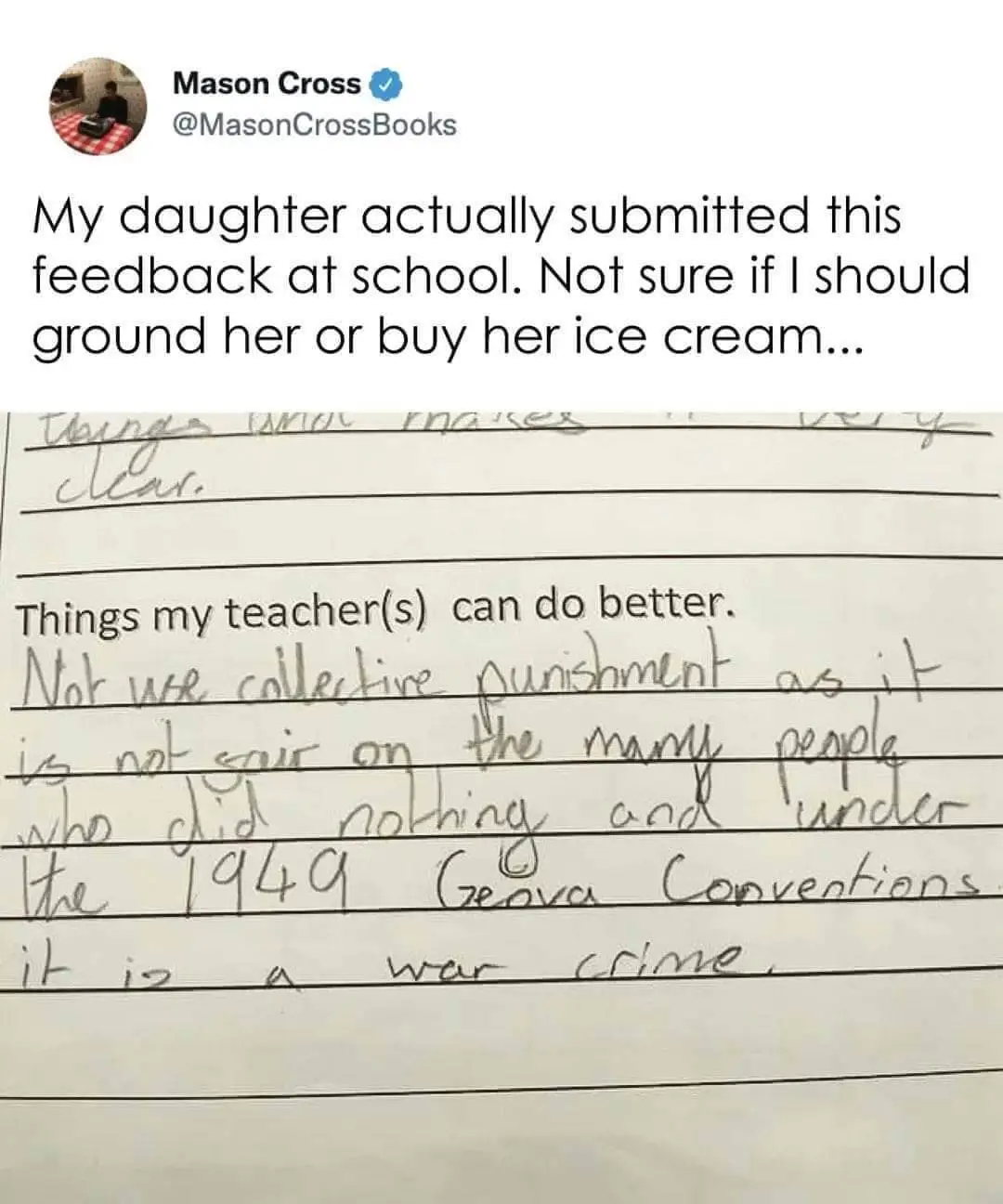

It began, as so many modern parables do, with a child who told the truth—and a parent who shared it. The image was ordinary: a school feedback form, completed in pencil, uneven in its lines, confident in its voice. The caption read: “My daughter actually submitted this feedback at school. Not sure if I should ground her or buy her ice cream…” The handwriting was unmistakably that of a child, but the sentence was thunderous in its clarity:

“Not use collective punishment as it is not fair on the many people who did nothing and under the 1949 Geneva Conventions it is a war crime.”

In the days that followed, that single photo would set off what became affectionately dubbed #Avagate, a hashtag storm that pulled thousands of people into reflection, memory, humour, and outrage—because Ava had not simply voiced a grievance. She had named an injustice that lives in the bones of almost every person who has ever sat through silence for talking, lost recess for someone else’s outburst, or learned that fairness often ends at the classroom door.

The viral moment revealed something we all already knew

The internet does not usually pause for matters of educational discipline. But something in Ava’s response—its righteousness—cut through the usual noise and struck a collective nerve. Ava had said what generations of children had felt but rarely been invited to articulate: that group punishment offends our sense of justice long before we know how to spell “Geneva.” That dignity, though unspoken, is a birthright children feel intuitively. That punishment, when misapplied, is remembered.

And so the world laughed and shared and reminisced and—remarkably—listened.

-

Why is collective punishment ineffective?

Collective punishment is not an evidence-based disciplinary strategy. It fails to support the long-term development of student accountability, safety, or prosocial behaviour. Rather than fostering responsibility, it creates a climate of fear, mistrust, and alienation—especially for students already struggling with regulation, belonging, or…

Professor Laura Lundy brought the law to the laughter

In the wake of this cultural moment, Professor Laura Lundy, an internationally recognised children’s rights scholar and legal expert, offered a response that was both clarifying and celebratory. Her essay, “Do collective punishments in classrooms breach the Geneva Convention?”, opens with a wry concession: “In short – yes. Just not the one that an 11 year girl from Glasgow claimed that it did.” She affirms that while Ava’s legal reference was technically misplaced—the Geneva Conventions apply to war, not recess—the moral argument was sound, and in fact a different international legal framework does apply: the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child.

This convention, which Canada ratified in 1991, affirms that children have the right to be treated with dignity, to express their views, and to be free from degrading treatment. Lundy points out what many of us have long suspected: if children had been invited to write that convention themselves, it would surely have included an explicit clause against being punished for something they didn’t do. Still, the spirit of that prohibition is woven throughout the document, in its insistence that punishment must be proportionate, respectful, and individual—not communal, coercive, or shaming.

-

What replaced the strap in Canadian schools?

They took the strap away—or at least, they removed the physical instrument, the leather loop of institutional discipline that had once been the sanctioned mechanism of control in classrooms across the country. Even if we never felt it on our own skin, we…

Dignity is a right, not a reward

Ava’s comment is so powerful because it reveals how deeply unfair practices have been normalised under the guise of control, convenience, or classroom culture. Adults who would never accept losing their pay because a colleague misbehaved will still defend withholding recess from twenty children because one child shouted out. These punishments are framed as character-building, but what they build instead is resentment, mistrust, and a brittle sort of silence that rarely teaches anything but fear.

Lundy names this with precision:

“No adult would readily accept a punishment for others’ misconduct and yet we expect children to submit to this without objection.”

That dissonance—between what we accept for ourselves and what we demand from children—is at the heart of the injustice Ava so eloquently exposed.

When children speak, we are meant to listen

One of the quiet ironies of this story is that Ava was responding to a teacher’s sincere invitation for feedback. Her response was posted on the classroom wall—a gesture that could have marked a genuine commitment to student voice, had it been received with seriousness. Lundy praises this, noting that seeking student input is one of the most important ways schools can uphold the Convention’s requirement to

“seek and give due weight to children’s views.”

But listening is not an aesthetic. It is not the act of posting feedback on a bulletin board and moving on. Listening means being open to discomfort, to critique, to change. Ava did what we ask students to do: she named a problem. What happens next—what happens when a child tells the truth—is the real test of whether rights are honoured or performatively acknowledged.

-

Performative accessibility in British Columbia public education

Too often, accessibility in schools is performance, not practice. Symbolic gestures and endless buzzwords cannot replace the courage to name harm, take responsibility, and commit to structural change. Until then, access plans remain brochures—and inclusion a stage set.

Ice cream and justice are not mutually exclusive

In the most widely shared follow-up image, Ava stands beaming with not one but two ice cream cones, her father captioning the post, “the people have spoken.” This moment, light and joyful, functioned as a kind of referendum—a spontaneous, unofficial declaration that this child had done something brave, that she had spoken with moral clarity, that she deserved to be heard and celebrated.

This small act of public delight did something powerful. It reminded us that children do not need to earn respect through docility. That cleverness and critique can coexist with kindness. That a child can love her teacher, as Ava’s father confirmed, and still challenge her teacher’s practices. That love and resistance are not opposites.

Ava’s moment was brief, but its lesson endures

The real power of #Avagate lies in what it revealed about our collective conscience. Ava’s words, shared in a moment of pencil-scrawled honesty, surfaced a truth that many of us had long since buried: that justice matters to children, that they see through hypocrisy, and that their sense of right and wrong is often clearer than the rules we ask them to obey.

Professor Lundy offered a vital legal lens through which to view this event. But more than that, she affirmed that Ava was not being dramatic, or disrespectful, or wrong. She was engaging in rights discourse—playfully, bravely, and publicly. Her voice was exactly what every school should encourage: informed, critical, and unafraid.

Ava’s teacher

Kudos belong, too, to Ava’s teacher—whose decision to invite student feedback, and to do so in a way that felt open-ended enough for honest expression, laid the groundwork for this moment of clarity and cultural resonance; it is no small thing to create an environment in which a child feels secure enough to articulate dissent, to name injustice, and to trust that her words, however bold, will be read not as defiance but as participation; that invitation—offered in the form of a simple question about improvement—becomes, in this context, a quietly radical gesture, reminding us that the most meaningful forms of accountability often begin with the courage to ask, and the willingness to hear.

It should never happen again—and yet it does, every day

In classrooms across British Columbia and far beyond, collective punishment remains common. It is disguised as “logical consequences” or “natural outcomes,” but it functions as shame-by-proximity and power without specificity. Ava’s small rebellion, her quiet sentence with its grand citation, reminds us that children feel these harms deeply, even when they lack the language to name them.

-

What are all the names of collective punishment?

Collective punishment doesn’t always go by that name. In schools, this harmful practice is often hidden behind vague, everyday language. Families may not hear the words “collective punishment”—but they feel its effects when an entire group is disciplined for the actions of one or a few.