After watching my children endure eight years of institutional failure, eight years of exclusion disguised as discipline and support withheld under the language of inclusion, I have come to several conclusions.

Certain forms of suffering—like being agonised inside—do not draw support because they do not disrupt the adult’s flow, do not demand intervention with noise or force. And even when a child’s pain is visible enough, loud enough, dangerous enough to warrant action—like the child who strangles the teacher—whatever support is offered will vanish the moment that crisis softens. When the flailing stops, when the room is quiet again, the system declares the need resolved. Support is withdrawn.

I woke this morning wondering, again: Who decides this? Who determines what kind of agony deserves support, and what kind will be endured in silence? Who chooses which child is worthy of resourcing and which is quietly abandoned? Who decides whose suffering is legible—and whose is ungrievable?

-

Grievability and legitimacy in BC Schools

Disabled children are being pushed out of public education—and their families are picking up the pieces. This post examines who is seen as worthy of support, what it costs when systems abandon care, and why the quiet exodus from schools is not a…

Who decides who’s suffering counts?

School principals in British Columbia must operate within district allocations and must request additional staffing when needs exceed what was initially provided. Final authority over approving or denying these requests generally rests with district leadership (e.g. the Superintendent or designated directors), not the principal.

For example, one district’s hiring policy states that “the principal will make a recommendation to the Superintendent of Schools (or designate) and the Superintendent (or designate) will make the final decision.” SD85 Hiring Policy

In practice, principals apply to the district’s Student Support Services or Human Resources department for extra staff, and the district’s decision-makers evaluate whether to grant or deny the request bcedaccess.com. This chain of command ensures staffing decisions align with district-wide budget constraints, policies, and equity considerations, rather than being decided solely at the school level.

Assessing need and urgency

When a principal identifies that a student or group of students needs more support than current staffing allows, an internal triage process is triggered. At the start of each school year, districts in BC allocate support staff (e.g. Education Assistants, learning support teachers) to schools based on projected enrolment and known student needs (such as the number and category of students with special needs) delta-optimist.com.

This initial allocation is often formulaic because there isn’t time to individually assess every student’s requirements in September bcedaccess.com. However, districts anticipate that these “automatic” allocations may not perfectly meet actual needs, so they hold back a reserve pool of support hours. After a few weeks of school, once real student needs become clearer, principals can formally request additional staffing (“a patch”) from the district bcedaccess.com. These requests typically occur in the early fall (often by late October, after monitoring how well initial supports are meeting student needs) bcedaccess.com.

District Student Services teams or senior administrators then assess the legitimacy and urgency of each request. Urgent cases – for example, a student whose safety or learning is at serious risk without one-on-one support, or a classroom experiencing frequent violent incidents – are prioritised.

Principals must explain the rationale and evidence for the extra support, such as describing the student’s needs, documented incidents, or unsuccessful interventions tried so far bcedaccess.com.

The district may consult data like the student’s Individual Education Plan (IEP), any behavioural incident reports, and enrollment changes (e.g. a new student with complex needs arriving) to judge the request’s urgency. In some cases, district specialists (psychologists, inclusive education coordinators, etc.) might observe or review the situation to provide input.

This “triage” approach means the highest-need situations get addressed first. Indeed, BC teachers describe a reality in which schools must “triage the system,” creatively reallocating limited supports and “cobbling multiple small supports together” so that the most urgent student needs are met first bctf.ca. Less urgent support needs might be delayed or covered by stretching existing staff (for example, having one EA assist multiple students by “piggy-backing” schedules) bctf.ca if resources are scarce.

Data used in triage

Criteria for approving additional support staff typically center on demonstrated student need, impact on student learning/safety, and alignment with resource availability. Districts base decisions on “thorough assessments of individual student needs as they manifest within particular classroom environments and during specific school activities.” sbsurreystor.blob.core.windows.net In other words, evidence of how a student’s disability or behaviour is impacting their and others’ safety or learning in the current setting is crucial. Some key criteria and data points include:

- Severity of student needs: Does the student have a designation (e.g. severe autism, chronic health, etc.) or documented exceptional needs that were unanticipated in staffing? A higher level of need (such as complex medical or behavioural challenges) strengthens the case for extra support. However, districts emphasise that support is not strictly tied to a funding category – “the services they receive…must be based on each student’s unique individual needs…not on an automated category-based system” bcedaccess.com. In practice this means a student without a formal designation could still get support if their needs warrant it, while a designated student might not automatically get a full-time aide if not needed.

- Impact on safety and learning: Data on incidents (e.g. injury reports, violent outbursts, students or staff being unsafe) is weighed heavily. If a lack of support staff is leading to unsafe situations or missed learning opportunities, the district has a stronger legal and ethical obligation to act. For instance, if a class has seen repeated behavioural crises that a lone teacher and existing EAs cannot safely manage, the urgency for more staff is clear. Districts also consider whether not providing support would violate a student’s right to meaningful access to education (a human rights concern).

- Current support utilisation: The principal’s request may detail how existing support staff are already fully utilised or why they cannot be reallocated. District decision-makers might review the school’s timetable or support schedule to verify that all other options (reprioritising staff, adjusting groupings, etc.) have been exhausted. They seek to ensure that additional staffing is truly needed and not something that could be solved by different deployment of current resources. Many districts have an internal framework or tool for this; for example, some use an “EA allocation tool” to help principals plan and justify how support hours are used and why more are required sbsurreystor.blob.core.windows.net.

- Equity and comparative needs: Districts strive to allocate resources equitably across schools. A central team may compare the requesting school’s situation with others: Are there other schools with similar challenges? Is this school asking for significantly more support per student than average? Equity doesn’t mean every school gets the same, but rather that needs are prioritised fairly. One district document notes that “equity is considered in decisions about support allocations to schools, based on a variety of factors.” This can include the socio-economic context (some schools may have more high-needs learners overall), and whether the requesting school has already received other special resources. The goal is to use limited district-wide support hours where they will have the greatest impact.

- Budget and funding availability: A practical criterion is whether there is funding or a vacant position to provide the extra staffing. Districts receive supplemental Inclusive Education funding from the province based on student designations, but this is a finite pool. Districts often hold a contingency reserve of support staff hours/funds to deploy mid-yeardelta-optimist.com. If that reserve is depleted or budget is tight, the bar for approving a request might be higher (unless a legal obligation makes it unavoidable). The Delta School District, for example, explained that it allocates EAs based on projected needs, then adds more after the fall enrolment count when provincial funds are confirmed, and “continues to add EAs throughout the remainder of the school year as needed using its reserve fund.” delta-optimist.com This indicates that when genuine needs arise, districts do try to fund additional support, but fiscal limitations can slow the response. In some cases, if no funding is immediately available, a request might be put on hold or partially granted (e.g. a part-time support instead of full-time) until resources can be found.

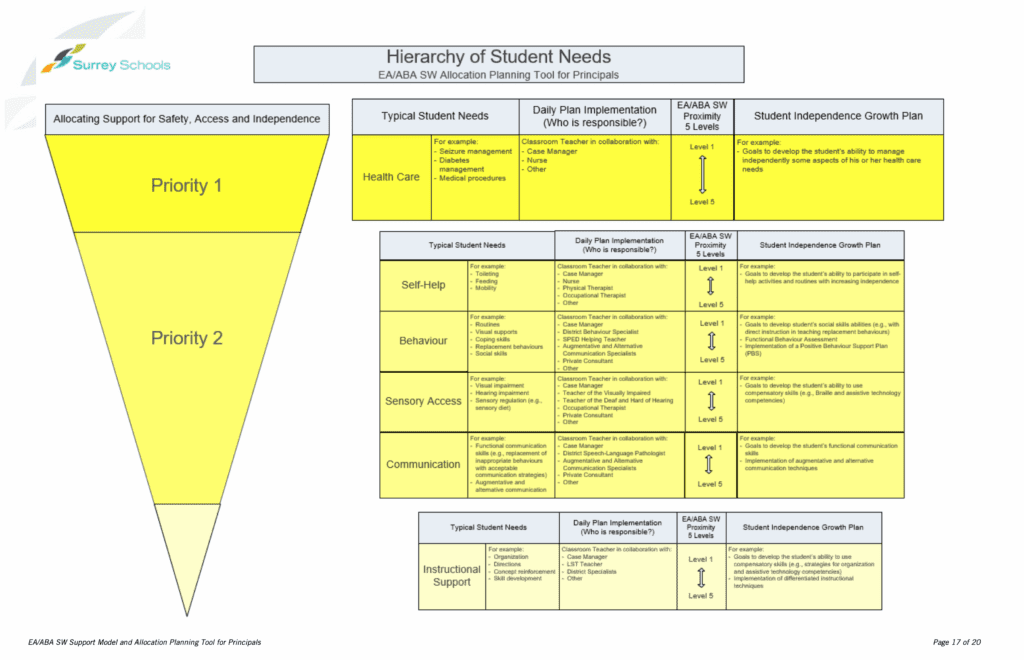

Hierarchy of student needs

The diagram is a decision-making aid for school principals to allocate EA (Education Assistant) or ABA SW (Applied Behaviour Analysis Support Worker) support based on student needs. It explicitly prioritises safety, access, and independence, and uses a tiered model to guide staffing decisions.

Visual Structure

The visual layout is shaped like an inverted triangle, indicating a hierarchy of support needs, from highest to lowest priority:

Priority 1 – Health Care

- Examples: Seizure management, diabetes management, medical procedures.

- Responsibility: Led by the classroom teacher in collaboration with case managers, nurses, or other medical professionals.

- Proximity Level: Scaled from Level 1 (most intensive) to Level 5 (least intensive).

- Independence Goal: To help the student manage their own health care needs to the extent possible.

Priority 2 – Other Domains of Need

Divided into several key areas:

Self-Help

- Examples: Toileting, feeding, mobility.

- Supports: Occupational or physical therapists.

- Independence Goal: Participation in self-help with growing independence.

Behaviour

- Examples: Routines, coping skills, replacement behaviours.

- Supports: Behaviour specialists, SLPD, autism consultants.

- Independence Goal: Social skill goals, FBA implementation, positive behaviour supports.

Sensory Access

- Examples: Visual/hearing impairments, sensory integration.

- Supports: Teachers of the visually/hearing impaired, OTs.

- Independence Goal: Use of compensatory strategies and tools.

Communication

- Examples: AAC use, language delays, social communication.

- Supports: SLPs, communication specialists.

- Independence Goal: Development of personal and assistive communication strategies.

Instructional Support

- Examples: Organisation, task initiation, transitions.

- Supports: Learning support teachers, district specialists.

- Independence Goal: Cognitive strategies for academic independence.

Key Mechanisms in All Areas

- Each domain includes a “Daily Plan Implementation” section that outlines team roles.

- Each area features a “Proximity Scale” (Levels 1–5) that informs how physically close and constantly available the support must be.

- A Student Independence Growth Plan is tied to every area, reflecting a commitment to capacity-building, not just supervision.

Bottom Line Summary

This framework centres student safety and access, but its deeper objective is fostering student independence over time. Supports are to be planned collaboratively and adjusted based on how close and constant the assistance needs to be, with a long-term goal of reducing reliance through intentional skills development.

Sexist, ableist, and compliance-obsessed

This so-called Hierarchy of Student Needs from Surrey Schools cloaks institutional neglect in the language of planning, appearing evidence-based while enshrining a model that centres visible disruption, physical safety, and compliance training over lived suffering, boundary violation, and masked distress. It presents itself as objective, but it encodes deeply gendered and ableist values about what counts as a crisis, who gets urgent support, and what kind of child is allowed to fall apart without consequence.

A child like my daughter—frozen with fear, starving from anxiety, unable to escape, unable to be heard, touched against her will by a boy who is also unsupported—would be placed low on this pyramid of priorities.

Just a PArent

She would be understood as passive, not endangered; quiet, not struggling; persevering, not in pain, independent. And because this tool ranks needs based on outward appearance and staff-centred interpretations of risk and liability, she would be excluded from emergency intervention precisely because she has learned to endure.

-

Our goals are not the same: ableism in bc public school

I want my children supported to grow and learn; schools uphold ableism by demanding they mask compliance or feign helplessness for support.

What the hierarchy values—and what it refuses to see

This tool rewards children who explode, not those who implode. It privileges conditions that come with a nurse’s protocol, a seizure log, a glucose monitor, or a visual cane—over those that are emotionally complex, socially coded, or invisibly traumatised. And within that logic, it quietly punishes the children who need support but do not ask, who freeze, who fawn, who hold their breath for eight hours, who stop eating, who whisper their truth once and then retreat forever when it is ignored.

By isolating health care at the top, the framework reduces vulnerability to medical technicality. By placing communication, sensory, and instructional support below behaviour and self-help, it subordinates internal experience to external function. And by insisting on an “independence goal” for every category—without honouring that some dependence is necessary, valid, and relational—it implies that any ongoing support is a failure rather than a right.

-

Apparently, starving yourself isn’t a serious mental health condition in VSB

There is a kind of harm that unfolds slowly — a hunger that accumulates across weeks and months, tucked beneath the surface of routines and well-meaning systems. My daughter is autistic, has ADHD, and a feeding disorder called ARFID. She eats quietly, cautiously,…

-

Not sick. Not fine. Not supported. Sexism in Vancouver School Board.

They said she was doing well. They said it with the softness of authority — that practiced tone that suggests neutrality while sidestepping consequence — a tone I’ve come to recognise as institutional, not personal, and absolutely not maternal. They said she was…

Where is the category for sexualised harm, for consent, for cumulative fear?

There is no place in this structure for children harmed by their peers, especially not if those harms are framed as behavioural misunderstandings, developmental mismatch, or lack of impulse control. There is no space for a girl who feels terror but sits still. There is no support plan for a child whose suffering arises from staff inaction or institutional betrayal. There is no line item for a girl’s dignity, for her silence, for her resistance disguised as cooperation.

Instead, her needs are filtered through what the staff already value: visible needs, fixable problems, staff-legible behaviours. Instead of asking what the child is surviving, the team asks how close they must stand to supervise. Instead of treating relational safety as foundational, they treat it as secondary. And instead of believing that children know when they are unsafe, they impose a proximity scale that ranks danger in degrees of staff discomfort.

Can principals be overruled?

Principals can be overruled in these staffing decisions. A principal’s request is essentially a recommendation; the district-level authority may approve it fully, partially, or deny it. There are a few common outcomes:

- Approved in full: If the evidence is strong and resources exist, the district grants the additional staffing. For instance, the principal might request an extra Education Assistant (EA) for a particularly high-need student, and the district assigns an EA (either hiring a new one or reallocating from its casual pool) to the school. Often this happens after the district’s fall funding adjustment, when they know what budget is available to add supportdelta-optimist.com. Districts acknowledge that initial allocations are adjusted once actual needs are verified, and they “allocate additional EAs with the funding received at that time” delta-optimist.com. They also tap into reserve funds during the year for emergent needs.

- Partial or alternative support: In some cases, the district might modify the request. They may provide less staffing than requested or a different kind of support. For example, instead of a full-time EA, the school might get a part-time worker or short-term specialist support. Alternatively, the district could deploy a behaviour consultant or itinerant specialist to help the school implement strategies as a first step, rather than immediately adding an EA. This sometimes occurs if the district believes the issue might be managed with expertise or training rather than extra personnel, or if they want to see if a smaller addition of support suffices before committing more. Principals can feel overruled if they asked for one solution and the district offers another. However, this compromise is often positioned as a way to meet the need in a different manner given limited resources.

- Denied or deferred: A request may be denied outright if the district concludes it’s not justified or not feasible. Common rationales for denial include: the student’s needs can be met with existing support (perhaps through re-organizing support blocks or expected improvement with current interventions), the data doesn’t show an urgent safety/learning risk, or budget/staffing shortages make it impossible. Sometimes district officials might suggest that the school try other interventions first. In the background, districts must triage across many schools – if every school requested extra staff, there would be a huge shortfall, so they only approve those deemed most critical. One Ontario report on special education noted that funding constraints create “a triage system of special education in which only the most needy are served,” and others receive less support – this is often true in BC as well, where only the highest-urgency cases get additional staffing quickly bctf.ca. Principals may be frustrated if a request is denied, especially if they feel it leaves a student without adequate help, but they can be overruled on the judgment that the district must prioritise even more urgent cases or simply cannot afford the extra staffing at that time.

When a principal’s request is overruled or only partially met, typically the district provides a rationale. For example, they might explain that “due to years of financial constraints… budgetary decisions [must have] the least negative impact on students” overall delta-optimist.com – implying the district is doing its best to allocate scarce resources fairly.

They may encourage the school to reapply later or note that the situation will be monitored. Importantly, legal and policy frameworks in BC give principals and parents recourse if they feel a student’s needs are being neglected: under the School Act’s appeals process (Section 11) or through Human Rights complaints, a decision to deny support can be challenged. In fact, the BC Human Rights Tribunal has accepted complaints alleging that failing to provide an EA for a student who needs one is discrimination on the basis of disability speakingupbc.com speakingupbc.com. Knowing this, districts are cautious – they must be able to defend that any denial still meets the student’s educational needs to the point of “undue hardship.” This legal backdrop means outright denials usually occur only if the district genuinely believes the request is not necessary or if they have an alternate plan to accommodate the student.

Legal and ethical obligations in staffing decisions

Legal obligations play a significant role in the triage process for support staff. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and BC Human Rights Code require that students with disabilities be accommodated in school to the point of undue hardship. This has been upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada, making it effectively “the law of the land”that support for students cannot be arbitrarily withheld if it’s needed for them to access education bcedaccess.com.

Practically, this means that if a student’s disability-related needs clearly demand additional support, a district faces a legal imperative to provide accommodations (like an aide, specialised instructor, or other resources) unless doing so is prohibitively difficult financially or otherwise. Ethical standards in education similarly hold that every student should have equitable access to learning; school districts publicly commit to inclusion policies and to “providing the necessary supports” for diverse learners www2.gov.bc.ca.

The BC Ministry of Education’s Inclusive Education policy manual advises that when “resources available at the school level have been exhausted,” districts should have a “mechanism in place to provide additional assistance to the school using district-level resources.” www2.gov.bc.ca In other words, the system is expected to step up with district supports if a school cannot meet a child’s needs alone.

These obligations factor into decision-making by creating a “floor” of support that must be met. If denying a request would likely breach a child’s right to an appropriate education, the district is compelled to find a solution. Even if budgets are tight, districts may reallocate funds or use contingency reserves in such cases, because the cost of failing to accommodate (in human rights damages, legal fees, or harm to the student) is higher. For example, some families have filed human rights complaints when support was denied, and the tribunal’s willingness to hear these cases speakingupbc.com speakingupbc.com puts pressure on districts to avoid outright refusals without solid justification.

Additionally, WorkSafeBC and occupational health regulations create an obligation to ensure staff have a safe work environment. If lack of support staff leads to teachers or EAs being injured by a student, the district could face WorkSafe violations. This legal risk pushes districts to approve extra help in situations of severe behavioural danger both to protect students and staff.

Ethically, school district leaders must balance fairness and compassion. They consider not just the letter of the law but the moral responsibility to support each child’s dignity and potential. Even when a principal’s request doesn’t meet an obvious legal threshold, ethical considerations might sway a decision. For instance, a student without a formal designation might be struggling profoundly – there’s no legal requirement to provide an aide, yet an ethical lens would ask, “What is the right thing to do for this child’s well-being and learning?” Districts also weigh the cumulative impact on school communities; if a principal warns that without more help, an entire class of students (and the teacher) will suffer, it becomes an ethical leadership decision to intervene if at all possible.

Despite this legal architecture, access remains deeply dependent on adult interpretation, administrative capacity, and the child’s perceived legitimacy

-

She’s agonised inside and that doesn’t count?

Much of this unfolded in 2022 and 2023, during a period when my daughter remained undiagnosed as autistic, unsupported in any formal way, and largely invisible to the school system. The patterns described here continue to shape our lives. In this essay, you’ll…

In summary

In summary, BC school districts use a structured yet flexible triage process to handle principals’ requests for additional support staffing. Principals initiate the request, but district personnel hold the decision-making power, aiming to allocate limited support staff to the schools and students in greatest need. The assessment process examines the urgency and legitimacy of the need through data and professional judgment, applying criteria like student need severity, safety concerns, and equity across the district. Principals can indeed be overruled – requests might be scaled down or denied – but such decisions are made against the backdrop of legal duties to accommodate students with disabilities and ethical commitments to support student success. As the BC Ministry’s guidelines emphasize, no school should be left to struggle alone once its own resources are exhausted: the district must have a mechanism to provide additional supportwww2.gov.bc.ca. In practice, while budget constraints force a triage (often only the most pressing cases get an immediate staffing “patch”), the guiding principle is that students’ needs drive these decisions. When a genuine need is demonstrated, especially one impacting a student’s right to an appropriate education or a safe learning environment, districts will strive to find a way to approve and fund the necessary supportbcedaccess.comdelta-optimist.com. This dynamic interplay of policy, evidence, and compassion defines how BC school districts triage and decide on principals’ requests for extra support staffing.

The training of detachment

When I ask how educators come to accept certain levels of agony, I return to the structure in which they are asked to endure. 26 children per room. Support waitlists that outlast the school year. Plans to deliver, goals to meet, bodies in motion. A child sobbing for 45 minutes becomes background noise in a system.

Professional detachment often emerges not from cruelty but from psychic necessity. Staff learn to pause, to observe, to wait it out because the system makes caring untenable. When showing concern results in punishment, delay, or more paperwork, a form of strategic numbness takes hold. And over time, that reflex becomes culture.

I wonder, still, whether some teachers remember the first time they failed to intervene—whether they revisit that child’s face in moments of stillness, whether they believe they’re keeping the peace, and whether they ever ask who is being asked to hold it.

Agony as disruption

What gets counted as suffering often depends less on intensity than on disruption. A scream will earn a call home. A broken pencil may trigger a behaviour chart. But a girl who withdraws, who scratches her arms silently, who wishes herself out of existence without ever raising her voice—her agony disrupts only those willing to witness it.

In too many classrooms, distress becomes visible only when it compels a response. Quiet grief is misread as growth. Stillness is rewarded. And the cost of surviving quietly is buried beneath praise for resilience.

Institutional sedation

Across British Columbia, policies now speak of self-regulation and positive climate. These ideals hold value—but in practice, they are often deployed as a form of ideological sedation. Children who collapse inward are seen as delicate or immature. Children who express distress are managed, contained, redirected.

The goal becomes “getting back on track,” but no one asks whether the track itself is violent. Sticker charts for stillness. Tickets for good behaviour. Calm-down corners that are often the busiest place in the classroom. This is the pedagogy of sedation, not healing.

The cost of becoming ignorable

In systems that cannot respond, many children learn to disappear. They hold their breath. They swallow their grief. They become ignorable because they must. And they are praised for it—praised for composure, for maturity, for grace. Until they collapse.

And when the collapse arrives—as it always does—it is framed as sudden. As irrational. As inexplicable. Rarely is it understood as the logical conclusion of months or years of unseen agony.

What would it take for someone to say, at last and with certainty: Being agonised inside is enough. She deserves relief.

-

Poise as pedagogy

There is a cost to composure that institutions never count. When schools reward mothers for staying calm in the face of harm, they turn grace into a gatekeeping tool and punish those who dare to grieve out loud.

-

Debility versus disability: what the system cannot acknowledge

My son Robin took to bed two weeks before March break. He had been soldiering on through the aftermath of a school transfer the district assured us would help him, though his body told me otherwise from the first day he arrived. I’ve…