I lived in Nelson as a child. The racial diversity was low. I know it has increased over time, yet it remains a small community, and when a young child arrives from another country and is visibly a person of colour, that presence remains noticeable across the Kootenays. This context matters when reading district records. A neighbouring district, Southeast Kootenay, recently released an exclusion report that includes the child’s immigration origin from an African country as part of the rationale for a reduced schedule, revealing both a profound misunderstanding of re-identification risk and a troubling narrative habit that uses biography to justify exclusion.

Re-identification risk

In the census division Regional District of Central Kootenay, “European (non-visible minority/non-Indigenous)” was 88.64 % and Indigenous identity was 6.69 % in 2021. Wikipedia

So while I cannot point to a number that says exactly how many people from the country mentioned in one child’s reason or event African heritage for that region, the existing data show that non-visible-minority populations dominate and that minority origin groups are very small.

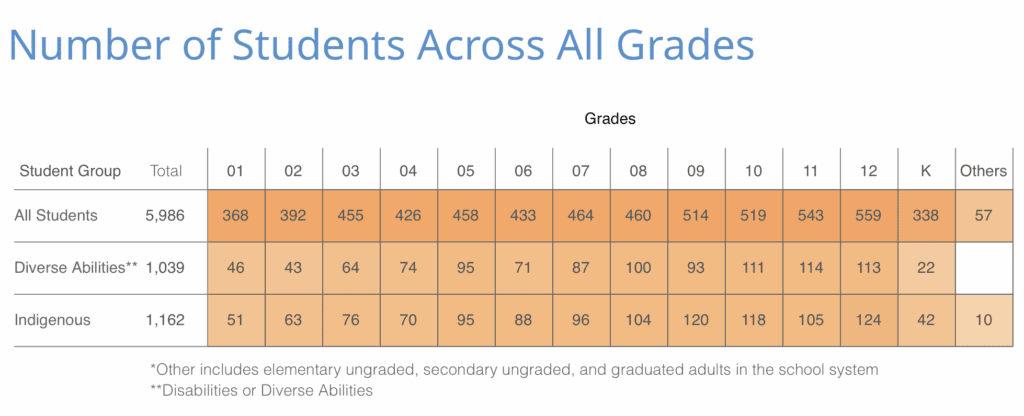

A district with ~338 kindergarten students can face extreme privacy exposure when a record includes a rare origin. Privacy risk is determined by the size of the subgroup that fits the description. When the attribute is uncommon, the subgroup collapses to a single child.

The district may have hundreds of kindergarteners, but it likely has only one—or at most a tiny handful—who match the excluded child’s biographical detail. A combination of unusual origin, behavioural description, exclusion description, and precise timeline produces immediate identifiability. The data becomes high-uniqueness, and the effective group size becomes N=1. Population size does not mitigate this risk when the trait is rare.

If a note referenced a child born in Calgary, the privacy exposure would be low because many could match. When the detail is unusual within a small community, it functions as an identifier, even without a name. Local knowledge makes this sharper still, because families in small regions often know who recently arrived, who is new to the area, and which children stand out within a small cohort.

Including such a detail in an exclusion record is therefore a privacy failure. It shows a willingness to use personal biography as explanation while overlooking the ethical and legal obligation to protect a child’s identity.

-

The architecture of responsibility in systems that harm

When a system produces predictable, patterned harm — exclusion, restraint, academic abandonment, institutional gaslighting, attrition framed as “choice,” disability-based discrimination — that harm arises from the structural design of the system itself, because structures generate outcomes with the same reliability that rivers carve their beds, and structures reveal the priorities…

Biographical justification for exclusion

Biographical justification is an institutional practice in which staff draw on a child’s personal background—immigration history, family context, disability label, or perceived difference—to explain reduced access to education. It appears descriptive and neutral, yet it shifts responsibility away from system-level limitations and onto the child’s biography.

Core function

Biographical justification reframes exclusion as a story about who the child is rather than what the institution failed to provide. It converts structural insufficiency into apparent necessity and casts reduced access as a tailored response to the child’s characteristics.

How it emerges

This practice arises when the institution lacks capacity and cannot meet its obligations. When resources are limited, staffing is inadequate, or supports are unavailable, staff often construct narratives that depict reduced hours as developmentally appropriate, protective, gentle, or aligned with the child’s supposed readiness. The story masks structural failure by implying pedagogical intent.

Narrative pattern

The narrative follows a consistent structure that protects the institution:

- centre the child’s difference

- foreground the family’s background

- frame reduced attendance as instructional, supportive, or therapeutic

- present staff as responsive rather than under-resourced

- omit any reference to legal rights, staffing shortages, or systemic barriers

The child becomes the location of the problem.

The institution disappears from view.

Privacy risks

Biographical justification often embeds unnecessary personal details in exclusion records. In small communities with limited demographic diversity, rare attributes sharply reduce anonymity and can identify the child even without a name. When timeline, behaviour, and schedule details are added, the subgroup collapses to a single child. The narrative becomes both a justification and an exposure.

Impact on educational rights

Biographical justification conceals a rights-based failure. It:

- obscures the child’s entitlement to full participation

- naturalises reduced access

- reframes systemic limitations as inherent traits

- masks the burden of chronic underfunding and inaccessible environments

The explanatory frame shifts from “the system could not provide” to “the child required less.”

Impact on families

Families encounter these notes as authoritative interpretations of their child. They can:

- reinforce deficit-based assumptions

- mislead later educators

- complicate advocacy

- entrench stigma in the child’s file

The narrative persists even when it reflects structural insufficiency rather than individual need.

Structural significance

Biographical justification reveals a system concerned with preserving its own legitimacy. It uses personal biography to naturalise exclusion, obscure institutional failures, and maintain the appearance of competence. A matter of educational rights becomes a biographical story. The institutional conditions remain unnamed.

Conclusion

The broader implication is straightforward: districts must stop using biographical justification to explain exclusion. Personal history, country of origin, family background, or perceived difference cannot serve as proxies for structural insufficiency. When these details appear in exclusion records, they obscure the system’s responsibility and convert a rights-based failure into a narrative about the child. They also generate unnecessary privacy risk, especially in small communities where rare origins or attributes identify individual children with ease.

Future reporting should adopt a different interpretive frame. When a child struggles to attend full-time, the explanation should begin with the institution’s readiness, capacity, and supports. Immigration status should not be interpreted as a reason for exclusion. It should be understood as evidence that the school underestimated the level of support required and therefore provided insufficient scaffolding for a successful transition to full-day participation. This shift matters because it aligns the narrative with the child’s rights, the institution’s obligations, and the structural conditions that shape access.

A reporting system that avoids biographical justification will produce clearer data, safer records, and a more accurate account of institutional responsibility. It will also help districts recognise the underlying patterns that drive exclusion and develop responses grounded in support rather than story.

-

The New Westminster submission to the Ombudsperson

Kudos to New West for being the first district I’ve identified to have released their report to the Ombudsperson. The New Westminster submission provides ~three years of exclusion data incidents organised by school, grade, and duration. The tables show concentrated exclusion activity in middle-years grades, consistent reliance on Code of…