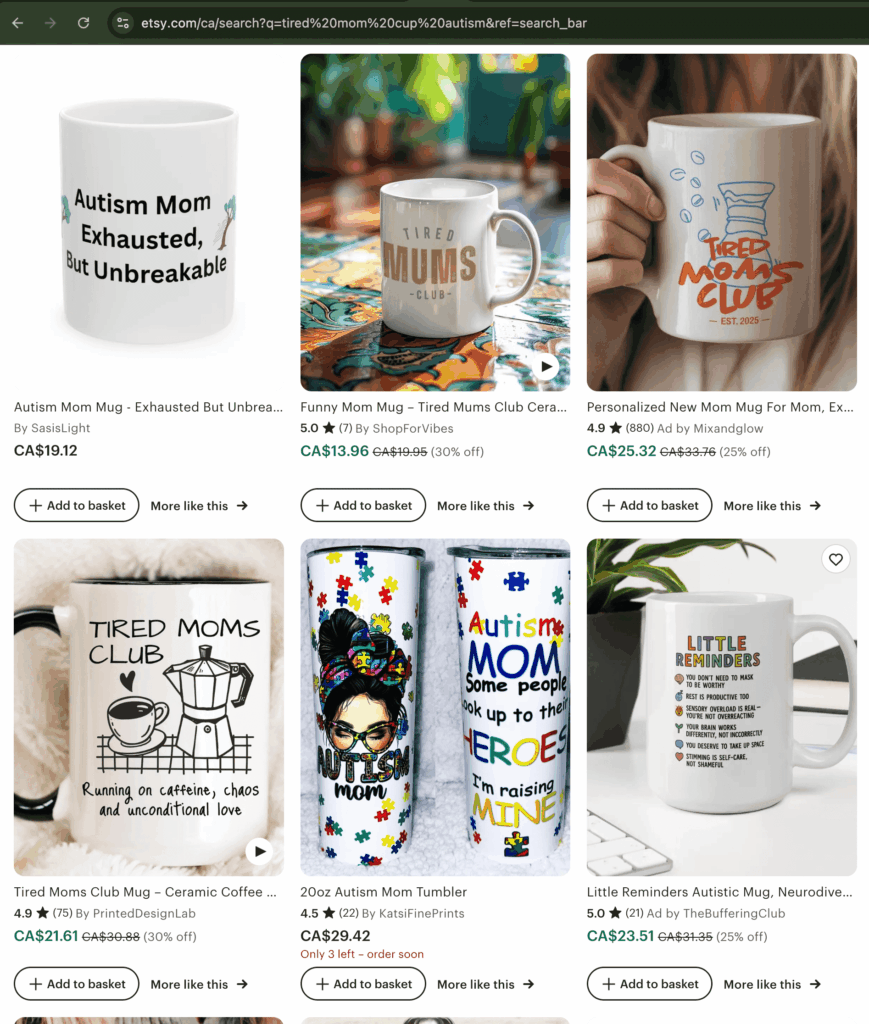

I keep seeing these memes circulating, which transform exhaustion into an aesthetic and valorise debility, like ‘look at how resilient I am!” I keep thinking about an image of a woman in pyjamas holding a Stanley cup, with a caption like “the mom life,” written as though wearing the same clothes for days is a charming milestone in personal freedom. The meme tells us we have evolved past caring what we look like, as though this represents liberation, when the truth for many of us is that personal hygiene drops on the priority list because the structures around us extract every workable minute of the day.

For me, it is not a personality trait; it is the consequence of navigating an excruciating school system with autistic twins, managing my own capacity, negotiating hostile or indifferent institutions, and trying to meet human needs under conditions shaped by austerity and ableism.

This entire aesthetic—the cozy burnout, the self-deprecating resilience, the look at me thriving in my depletion—is compliance culture operating as designed. It converts structural violence into personal quirk. It asks women to see exhaustion as a relatable brand, something to be embraced, shared, and lightly mocked, instead of something that reveals capitalism’s appetite for our unpaid care labour. It nudges us into a kind of psychic domestication where we stop expecting more because we are told that our frayed edges are proof of devotion rather than evidence of systemic harm.

I am glad I no longer wear uncomfortable office clothes, which have always felt like artefacts of someone else’s expectations, yet the real story remains the structural pressure that turns even basic self care into a luxury.

On being resilient, capitalism, and compliance culture

The aesthetic of fatigue encourages a sentimental reading of these compromises, asking us to celebrate the ways our lives have been made smaller and to treat survival as proof of devotion. It frames the erosion of capacity as charm and authenticity, and it disguises the structural conditions that produce that erosion. This is the influence of capitalist structures, compliance culture repackaged as relatability, a form of emotional marketing that turns scarcity into a personal brand. These memes do not challenge the systems that underfund education, fragment care, and leave families unsupported; they encourage us to see our exhaustion as an acceptable state, even a flattering one.

The silver-lining genre works the same way. These messages urge us to find a small delight in the chaos of the day, to treat a lukewarm coffee or a chaotic dinner as evidence that life still holds sweetness, yet the sweetness for me lies in understanding the system, not in pretending that my compromises taste good. My McDonald’s last night was salty, scratchy, and painful to swallow; it filled a need, nothing more. I refuse to imagine it as a moment of joy. The pleasure came from recognising that the bar of “we are fed” should never be the benchmark we celebrate.

Resilience culture and the treatment of children

I lose my patience every time someone at an IEP meeting says my children are resilient, as though their endurance should reassure me instead of alarming me. It is the same logic that celebrates adults for surviving on four hours of sleep and three cups of coffee; it is simply applied to children with even less power to refuse.

Resilience has become one of the system’s favourite buzzwords, a convenient moral coating for structural abandonment, because it allows educators and administrators to frame a child’s struggle as evidence of admirable character rather than evidence of unmet need.

Just a Parent

There is a difference between productive challenge—like working through a hard math concept with appropriate instruction—and the chronic overwhelm that comes from trying to learn in an environment that misreads you, underserves you, and overtaxes your nervous system. Struggle in the presence of support can build confidence. Struggle in the absence of support erodes the self. And when institutions valorise the latter, they disguise harm as growth and call it education.

The aesthetic model of disability

In The Aesthetic Model of Disability (2021) disability is described as not inherent to the body but emerging from rigid expectations, fixed environments, and normative standards that define what “counts” as valid performance. Disability appears “dependent on context,” and if the environment adapts, a person does not necessarily experience disability.

The school insists the child must adapt and disability is produced by the refusal of the environment to shift. Normative standards create exclusion, as when an artist insists that participants must conform to certain techniques or stamina levels, thereby constructing their disability through environmental constraints.

The chapter highlights how institutions misread difference as deficit, recoding non-normative behaviour as “lack,” “slow learning,” or “inadequate stamina” — mirroring schools that interpret sensory overload or distress as behavioural failure or insufficient grit.

Aestheticising masking

For disabled and neurodivergent children, this becomes even more dangerous. They are told, directly or indirectly, that their task is to try harder, mask more effectively, calm themselves quickly, endure more friction, and demonstrate a kind of stoic competence that adults read as resilience.

In reality, what they are doing is surviving in conditions designed for their despair and disappearance. Their distress is reframed as a test of character. Their adaptations are recast as inspirational. Their pain is folded into the institution’s narrative about perseverance. They are scapegoated to maintain austerity. The more they endure, the more the system congratulates itself for producing “resilient kids,” while quietly avoiding the investment that would allow those kids to learn without fear.

And the fear matters. Feeling unsafe at school, feeling hunted for sport, feeling like every day requires vigilance—none of that resembles the kind of difficulty that teaches skill or grit. It is traumatic and when an institution interprets that survival as resilience, it reframes the child’s suffering as an asset rather than a warning. It tells them that if they simply push themselves harder, they will become good. As if they are not already trying to fucking hard!

This is why the resilience narrative feels so hollow to me. It hides structural scarcity behind emotional language. It takes the pressure of institutional failure and places it squarely on the child’s shoulders. It allows the system to congratulate itself for producing hardworking, adaptable, “resilient” students instead of admitting that these students needed support and did not receive it. And for vulnerable children—children already contending with stigma, sensory pain, unpredictable peers, inaccessible routines—the message that they should embrace their hardship as character-building becomes a pathway to deeper harm. They internalise the idea that success requires self-erasure. They believe that surviving unsafe conditions is their responsibility. They assume that their suffering is normal, perhaps even virtuous.

It is the same compliance culture that tells adults to celebrate coping instead of demanding transformation. It is the system praising the child for enduring.

The demand to “build tolerance” for the classroom

And then there is the phrase I hear far too often: building tolerance for the classroom. It is presented as a neutral objective, as though the child’s task is to expand their capacity to endure an environment that has made no comparable effort to adjust to them. The language itself reveals the hierarchy: the room stays fixed, the routines stay fixed, the expectations stay fixed, and the child must cultivate tolerance until the friction stops being noticeable to the adults in charge. It mirrors the way adults are encouraged to build tolerance for burnout—become more resilient, lower expectations, adapt privately to public scarcity.

The idea of “building tolerance” sounds therapeutic, even progressive, yet in practice it often signals an institution unwilling to examine why the classroom is so overwhelming in the first place. Instead of asking whether the sensory load is too high, whether the schedule is too rigid, whether the social environment is predictable, whether the work is accessible, or whether the staffing is adequate, the system reframes the problem as a child’s deficit in tolerance. The environment becomes unquestionable. The child becomes the site of intervention.

For neurodivergent children—especially autistic children, children with PDA profiles, children with trauma histories—this framing becomes extremely dangerous. It teaches them that distress is a test they must pass. They must stop listening to their feelings and endure discomfort to be good.

It suggests that suffering has pedagogical value, that perseverance is inherently good, that tolerance is a virtue to be cultivated, and that refusing to endure an overwhelming environment signals weakness rather than wisdom. This becomes a self-fulfilling loop. The child is congratulated for pushing through discomfort. Their endurance is labelled resilience. Their distress becomes invisible to the adults who believe they are “adjusting.” No one intervenes because the narrative has already determined that the problem lies within the child’s capacity to tolerate, not in the institution’s capacity to transform.

Learned helplessness and cognitive exhaustion

The truth is that my children have been warehoused. People recoil when I use that word, as if it is too harsh or too accusatory, yet it is the only word that describes what is happening. My daughter is now almost two years behind in math, and she has decided she does not like to read. No one at her school has made any serious effort to understand her literacy level because they decided early that the primary task for autistic girls is to “build tolerance” for the environment rather than receive an education that responds to their actual needs.

Her academic drift is not a mystery. It is the predictable consequence of years spent in classrooms that misinterpret her needs, treat masking as competence, and read her distress as a personal issue instead of evidence that the environment is inaccessible. When a child’s skills erode this dramatically, the school should act with urgency, not resignation.

There is no pedagogical framework that justifies deprioritising academic learning for any child. There is no ethical justification for accepting the loss of a child’s love of reading as collateral damage. What exists is austerity — schools rationing labour, cutting corners, and quietly pushing children to the margins because their needs require attention the system does not want to provide. A bright autistic girl becomes the ideal target for neglect: assumed capable, assumed stable, assumed fine.

According to Consequences of Learned Helplessness and Cognitive Exhaustion (2017), when a person is repeatedly placed in situations where success is impossible, they enter a state of cognitive exhaustion — a diminished capacity to think clearly, generate solutions, or sustain effort. The theory (Sędek & Kofta) emphasises that this is not a personality flaw; it is a structural effect of uncontrollable conditions.

This state is defined as “diminished and less efficient usage of cognitive resources,” leading to difficulty tackling new or complex tasks, negative emotion, and performance decline. My daughter describes the emotional work of dealing with a teacher asking her to read the question again for math, when she has no clue as to where to begin to solve the question. It makes math horrible.

The study notes that when individuals repeatedly attempt a task that remains beyond their control, they become passive even in tasks they could do under better conditions — because the system has drained their cognitive resources. Children who endure overstimulation, under-support, or ambiguous expectations are not “building resilience.” They are entering states of cognitive exhaustion that resemble depression, vigilance, and passivity. Their apparent “calm” or “compliance” may be the shutdown described in this body of research.

Clarity, refusal, and political direction

I do not fault individuals for doing what they need to survive. I understand why people find solace in sharing the smallest details of their hardest days. I understand the impulse to claim agency by narrating depletion as resilience. Yet the industry that aestheticises barely getting by serves interests that are far larger than any single person’s story. It reinscribes scarcity as identity. It encourages compliance. It transforms structural abandonment into content.

My own comfort comes from clarity, from refusing to reframe distress as triumph, from insisting that our reduced capacity deserves care while our institutions deserve transformation. Fatigue becomes political the moment we refuse to make it beautiful.

-

The poison of silence: on complicity, healing, and speaking the truth

I had so much pain stuck in my chest and throat. Cancelled screams. Unsaid truths. Every meeting where I stayed quiet, every time I swallowed my words to seem reasonable, every time I hoped that portraying myself a…