When I told another mom recently—someone kind, someone well-meaning, someone whose son used to play with mine back when things were easier—that I was feeling fragile about him being home since March, and that it had all gotten heavier than I expected, she responded gently and said, “Would he like to come over for a playdate?”

Would he want to come over for a playdate?

And I froze because it showed me so plainly how invisible the truth has become, even to those who were once close enough to see it if they’d wanted to.

She didn’t know.

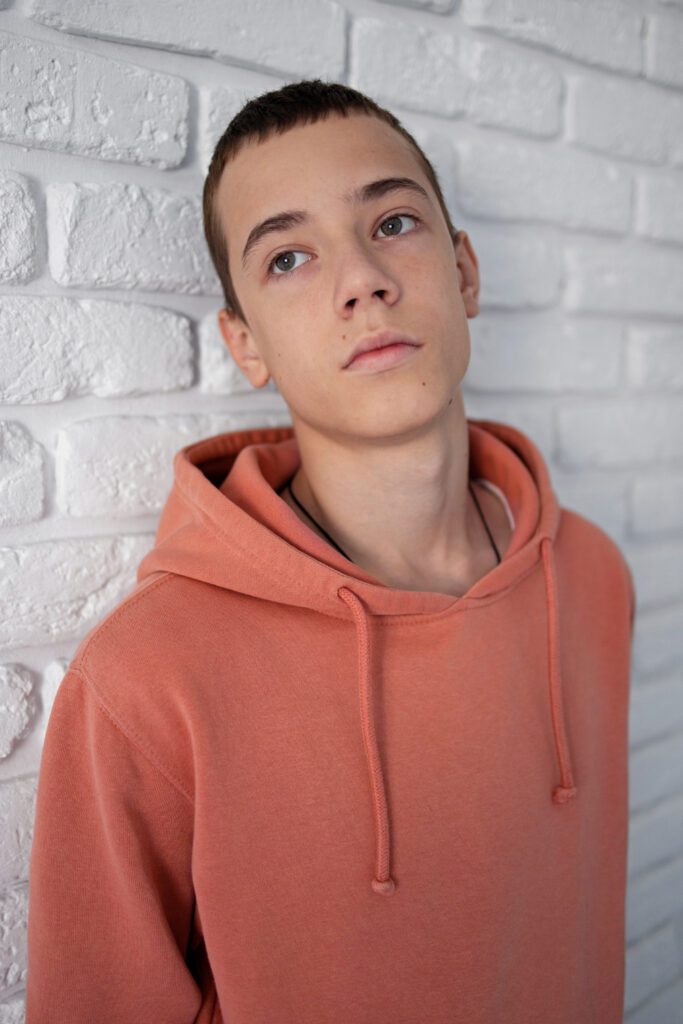

She didn’t know that my son barely gets out of bed anymore, that his body now takes up space like a grown man but his spirit hovers somewhere between shutdown and survival, that his eyes are dimmed in a way I cannot describe without falling apart.

She didn’t know that weeks ago, I called the police because I genuinely thought I might be hurt and I didn’t what else to do. That I’ve had to speak to a social worker.

She didn’t know. But I did. And I have known for a very long time that this could be the conclusion of these sad interactions with the school. Unfortunately, I come from a family of actuaries, and predicting risk is easy protecting from it is hard.

They thought I was the problem

I could see this coming for a long time. Cracks forming and I tried, again and again, to point them out, only to be met with the same strained smiles, the same passive resistance, the same weary implication that if I could just stop being so difficult, things might go better for everyone.

I was treated like a stick in the mud. Like a pedant. Like a bitch.

Like someone who refused to go with the flow, who always had one more concern, one more thing to say, one more sentence in an email that might have been better left unsent—because didn’t I see how hard they were already trying? This was treated as a defect like I might not be aware of their policies or practices and that they were trying hard under dire circumstances and I might need their situation explain to me again.

The principal told me more times than I can count that their goal was to have positive interactions, that they wanted to build relationships, to be strengths-based, to be kind.

And every time, I said something that, to them, probably felt like the opposite of kind.

I said, “He doesn’t want that.”

I said, “He needs declarative language.”

I said, “Your smile might be a trigger.”

I said, “The more you praise him, the less safe he feels.”

And it was like speaking another language—like trying to describe colour to someone who had only ever seen black and white, and who didn’t particularly want to imagine anything else. There must be something wrong with me if I don’t want to be positive.

-

Wait and see: a mother’s warning

Before kindergarten began, we told them—unequivocally, painstakingly, with as much specificity as we could muster—that our son had been harmed in daycare, that he had a long line of diagnoses and was awaiting an autism assessment, that his nervous system was thrashed, and…

Neuronormative school politics

The politics of school are neuronormative to their core—not just in pedagogy or policy, but in culture, in mood, in the soft tyranny of what everyone assumes is normal.

They believe in smiles. In cheerful greetings. In stickers and stars and “good job” on loop. They believe in tone of voice as a tool for motivation. They believe that children want to please and that teachers want to be pleased and that this dynamic is, somehow, universal.

And when a child doesn’t respond to that—when praise shuts him down, when demands feel like violence, when even kindness is filtered through a threat response—the assumption is that something is wrong with the child, or maybe with the parent, but never with the assumptions themselves.

So when I asked for declarative language—“It’s time to line up,” not “Would you like to come with us?”—I wasn’t just making a suggestion. I was asking them to break character. To step out of the roles they had been trained to play and speak in a way that was foreign to them.

And they didn’t want to.

They told me they were doing their best. That they were already stretched thin. That it was important to them to maintain positive energy. That they were already bending as far as they could go.

But what they never said—what they couldn’t quite admit—was that they didn’t believe me.

They didn’t believe that those little things mattered. Not really. Not enough to change.

-

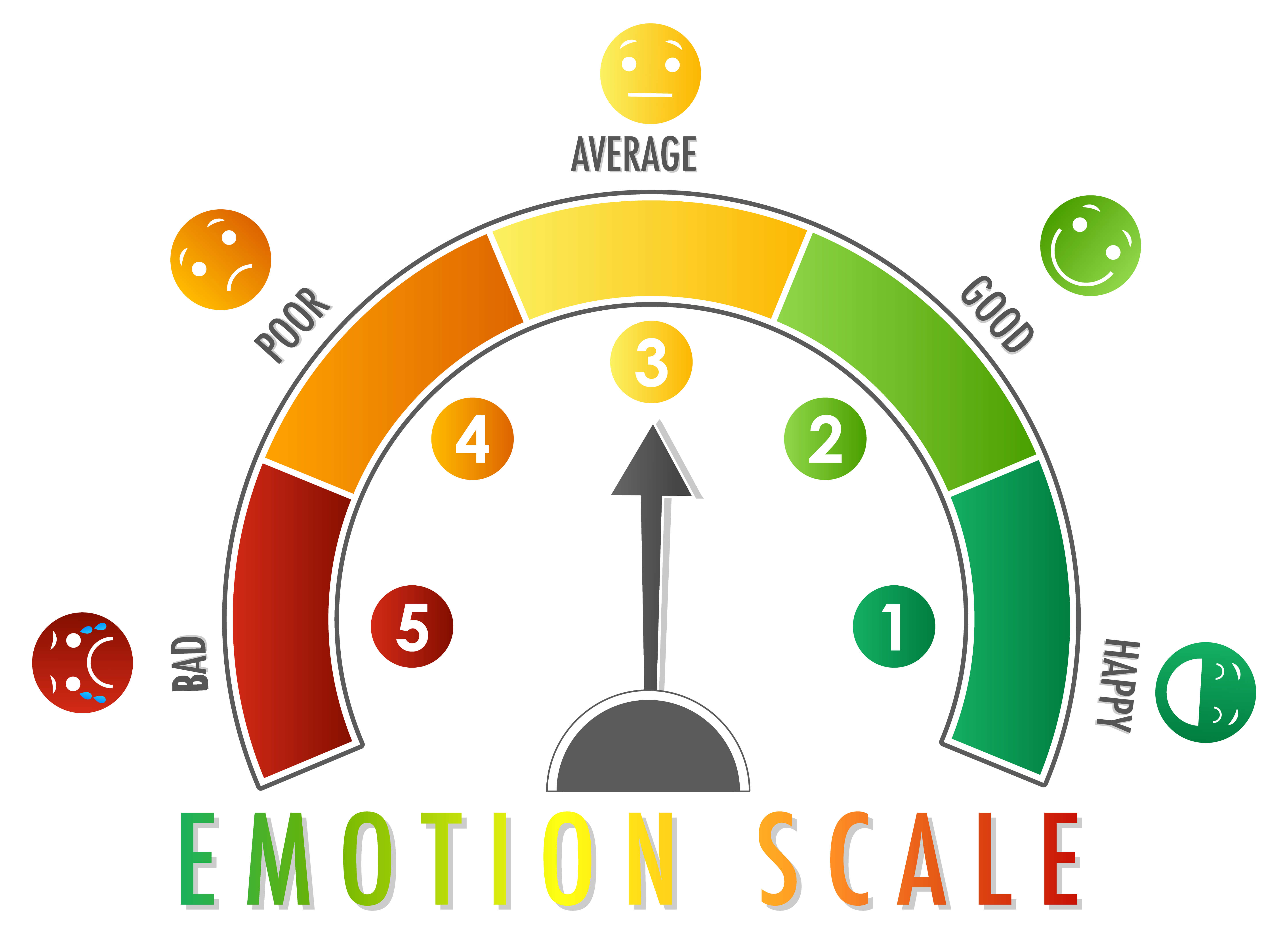

Regulation isn’t colouring a box: how neurotypical emotion models can harm autistic kids

The Zones of Regulation chart is made of four tidy boxes—blue, green, orange, red—a short list of emotions, each offering the illusion of clarity, simplicity, legibility. It’s a system that looks soft, friendly, and progressive, but that often functions as a mechanism for…

The unbearable cost of small things

People think fragility means weakness, or hypersensitivity, or overreaction. They think it means that the child—or the parent—is too thin-skinned, too reactive, too dramatic. But what I’ve come to understand is that fragility isn’t about emotion. It’s about load-bearing. It’s about thresholds. It’s about how many drops a bucket can take before it spills.

And my son—like so many autistic kids, like so many kids with a PDA profile—was already carrying too much.

Demand after demand. Change after change. Smile after smile that didn’t feel safe.

Every time they refused to adapt, every time they dismissed the strategy, every time they prioritized “relationship” over regulation, they added one more drop.

And now the bucket has tipped.

He’s not in school. He’s not okay. We are not okay.

And the worst part—the part I still can’t quite forgive—is that they were warned. Not just by me, but by every parent who came before me, every article, every whisper in the hallway, every desperate strategy shared in an online group at 2 a.m. by another mother trying to keep her child alive in a world that keeps saying it’s not that bad.

It was that bad. It is that bad. And still, they didn’t change.

If they had just tried

I keep thinking—no, looping, really, because it’s not linear, it’s not a clean question with a clean answer, it’s this sticky, constant, aching return to the same feeling in my chest—what if they had just tried?

Not perfectly, not all at once, not some fantasy version—but just tried, in good faith, to meet what I was asking for with the seriousness and the weight that it deserved.

What if, instead of assuming I was overreacting, or spiralling, or fixated on minutiae, they had paused—just for a moment—and asked themselves whether maybe, just maybe, the mother in front of them knew what she was talking about?

What if they had listened to me—not in that nodding, passive, I-hear-you-but-I’m-not-going-to-change kind of way, but really listened, with the full-body discomfort of having to rethink something they thought they understood—and accepted, however reluctantly, that for this child, with this nervous system, with this history, the rules were different?

What if they had been willing to try declarative language—not as a box to check or an experiment to humour me with, but as a genuine shift in their way of speaking, a reorientation toward what safety might look like for a child whose entire body goes on alert when asked a question?

What if they had believed me when I said that praise wasn’t praise, not for him, that he didn’t want to be told he was doing a good job, that the very structure of “goodness” was a threat in his world, a signal that someone was watching and measuring and waiting to reward or withdraw depending on compliance?

What if they had let go—just a little—of that deep cultural script about positivity and warmth and relationship as the only pathways to learning, and considered, for even a moment, that those things might land differently when a child is operating in survival mode most of the time?

What if they had made the effort—not because it was easy, and not even because it was guaranteed to work, but because they understood that the cost of not trying was something none of us could afford?

Would he still be in school?

Would he still be laughing?

Would he still be reachable?

Would I still be someone trying to explain this in the aftermath instead of someone desperately trying to prevent it?

And I don’t know. I will never know. That door is closed now.

But what I do know—what I can say, without needing to walk it back or soften the edge—is that I wasn’t being difficult. I wasn’t being petty. I wasn’t being dramatic or obstructive or irrational.

I was being precise.

I was being careful with the truth.

I was watching the structure shake and crack, and I was trying—gently, then firmly, then with every ounce of strength I had—to keep it from falling.

They thought I was a stick in the mud. But I wasn’t stuck. I was bracing for collapse.

And the worst part, the part that I still can’t say without my voice catching, is that I think if they’d really tried—really tried—we might not be here.