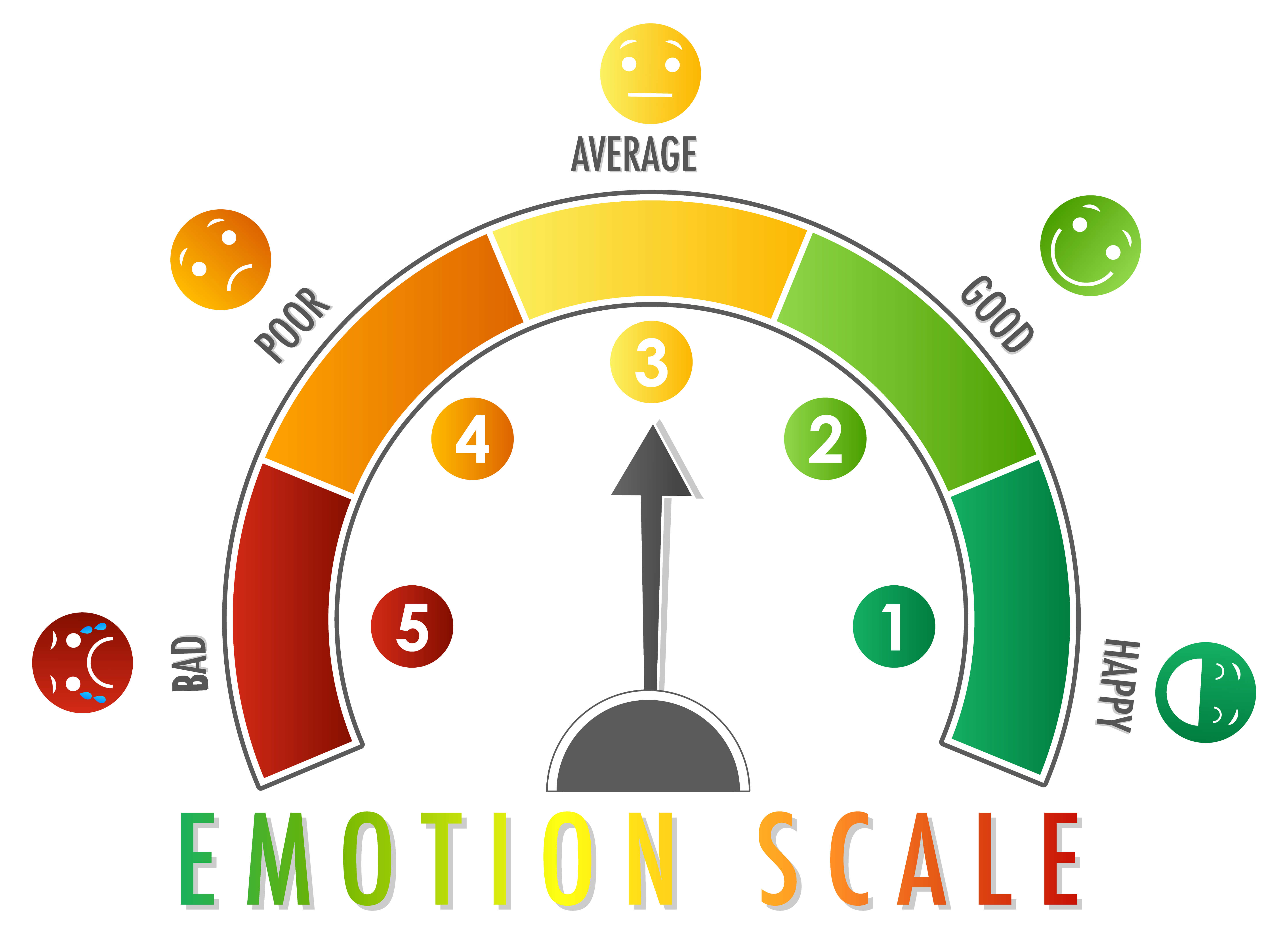

The Zones of Regulation chart is made of four tidy boxes—blue, green, orange, red—a short list of emotions, each offering the illusion of clarity, simplicity, legibility. It’s a system that looks soft, friendly, and progressive, but that often functions as a mechanism for shaping children’s expressions to fit the comfort and control needs of adults, rather than making space for the complex, layered, embodied experiences of children navigating emotional truths that don’t fit institutional expectations.

It’s offered in good faith, sometimes with gentle voices and calm corners and laminated visuals meant to support self-awareness and resilience—but for many autistic kids, and for the adults we became after years of flattening ourselves to survive these exact environments, the Zones chart is not a help; it’s another site of misrecognition, where the truth of our internal states must be translated, contorted, or performed in ways that deny their legitimacy unless they can be colour-coded and made manageable.

And when we cannot—or will not—fit our feelings into a neat little square, we are not seen as honest, or complex, or asking for help in the only language our bodies have learned; we are seen as uncooperative, avoidant, dramatic, or unwell.

Too much to be one colour

Ask me how I feel, and I might pause—not because I lack emotion, but because what I feel is not easily summed up in a single word or image or tidy category. In the span of a single moment, I might be grieving something I haven’t yet named, laughing at a private joke sparked by a stray thought, trying to tolerate the scratch of a tag against my neck, managing the background roar of tinnitus, registering the coldness of my ankles, and catching myself spinning through a long-form spiral of self-directed frustration while also noticing the peculiar angle of light on the floor and the urge to hyperfocus on something I haven’t yet articulated.

That state—a dense, multi-threaded tangle of sensory, emotional, cognitive, and physical experience—is both ordinary and unchartable, especially in a world that keeps asking me to pick a colour, name a feeling, or produce an answer fast enough to keep the adult’s attention, the group’s schedule, or the classroom’s behaviour chart on track.

I am not confused.

I am plural.

Do I contradict myself?

Song of Myself, 51

Very well then I contradict myself,

(I am large, I contain multitudes.)

Walt Whitman

Alexithymia—unspeakable knowing

Alexithymia—the clinical term for difficulty identifying and describing internal emotional states—is often misunderstood as a deficit of feeling, as though we are detached, dull, or numb. But for many autistic people, it is more accurately described as the experience of too much, too fast, too overlapping, or too unnameable, paired with a world that demands simplification, translation, and emotional consistency we may not be wired to perform.

Note: Autistic experience is deeply diverse, and while many of us live in a state of intense, layered, often overwhelming feeling that defies language, others describe something quieter: a muted or distant connection to emotion, an internal blankness, or a sense that feelings exist but are hard to locate, let alone describe. Both are valid expressions of autistic embodiment. Some people with alexithymia feel too much and can’t parse it; others feel very little and may struggle to detect emotional states at all—and some shift between those extremes depending on context, trauma history, masking load, or cognitive energy.

Being asked “how do you feel right now?”—in a tone that expects one word, one clean emotion, one right answer—while you are sifting through hours of context, bodily cues, social tension, delayed processing, relational memory, and the question of whether it is even safe to tell the truth in this space, can feel less like a request and more like a trap.

It’s saying “angry” because “frustrated, invisible, and unaccommodated again” won’t fit on the worksheet, or saying “fine” because you’ve learned that’s the fastest route to being left alone, or saying “sad” when you’ve already forgotten how many times today your mask has cracked and been repaired without comment or care.

And when therapy, school, or well-meaning adults insist that naming the emotion is the first step toward support—but punish, correct, or disbelieve us when the words don’t come easily, or come out wrong—it doesn’t feel like help.

It feels like betrayal.but punish or correct or disbelieve us when the words don’t come easily—or come out wrong—it doesn’t feel like help; it feels like betrayal.

When feelings become a performance

Many autistic children learn early that the safest path through systems built for neurotypical behaviour is to perform what adults expect to see, whether or not it’s honest, whether or not it reflects anything inside them at all. This performance often becomes so automatic, so rehearsed, so thoroughly conditioned by praise and punishment, that by the time we enter therapy, advocacy, or adulthood, we are still scanning the room for cues on how to appear ourselves—how to look like someone doing well, or doing the work, or doing what’s expected—even if we are terrified of people knowing how we feel inside.

Maybe we cannot understand—not because we are broken—but because we were never granted the words, the patience, or the humanity to express ourselves in the first place.

And so therapy, which is meant to be a space of honesty, becomes a kind of stage, where we sit with a professional who says “let’s talk about how that made you feel,” and we begin sorting through our catalogue of pre-approved phrases, facial expressions, and metaphors, hoping one will land well enough to get us through the session without shame, even though the entire process feels hollow, contrived, and estranged from the vivid but illegible experience of being who we are in a world that keeps demanding simplification.

It is not that we lack emotional depth.

It is that the tools we are offered have been carved from someone else’s shape of knowing, and every time we try to use them, we lose a little more connection to our own.

The colours become a cage

The Zones of Regulation model claims to teach children how to identify and manage their emotions by categorising them into four colour-coded states, each with its own traits and suggested strategies—but in practice, especially in schools, it often becomes a system of surveillance and correction, where children are asked to name their zone not as a form of self-awareness, but as a prelude to being redirected, reshaped, or praised for returning to green.

There is no space in the Zones chart for ambivalence, contradiction, overwhelm, or quiet joy; no room for non-verbal knowing, for non-linear time, for the child who is “in the yellow” but desperately wants to stay there because it means feeling alive for the first time today; and certainly no acknowledgement that some of us do not experience our internal states in separable, stackable units that can be colour-coded like traffic lights or indexed like flashcards.

When children are told, again and again, that “green” is the goal, “red” is a problem, “blue” is low-functioning sadness, and “yellow” is the warning before it all goes wrong, they begin to understand that what’s wanted from them is not truth but legibility—not real insight, but manageable expression—and many learn, quietly and skillfully, to say what the chart wants, not what they feel.

What regulation actually requires

Real regulation—the kind that builds long-term safety, relational trust, and internal resilience—is not a return to baseline in a colour-coded framework, but a grounded sense of knowing what your body is trying to tell you, trusting that your proprioception is valid, and having consistent access to environments and people who respond to those signals with care rather than coercion.

It means recognising that autistic regulation doesn’t always look like stillness or smiling or meeting the adult’s eye—it might look like stimming, pacing, retreating, repeating, tuning out, tuning in, lying on the floor (gravity is hard), or needing to talk at someone for ten minutes straight without interruption just to make space for breath.

It requires adults to stop demanding immediate clarity, to stop insisting that feelings be named before they can be supported, and to start creating conditions in which complexity is allowed, respected, and believed—even when it’s messy, slow, or contradictory.

We need adults who wonder

The goal of emotional support should never be to narrow the range of what’s allowed, but to expand the conditions under which people feel safe being fully themselves—not flattened, not translated, not made more convenient for someone else’s system, schedule, or script.

We do not need charts that tell us who we are. We need adults who are willing to sit beside us and wonder, gently, what it might feel like to live inside a body that processes the world like a symphony and a fire alarm all at once.

We need support that trusts our complexity, that makes room for our silences, that allows emotional truth to unfold without deadlines, and that recognises “I don’t know how I feel yet” as one of the most courageous and honest things a person can say.

That it’s okay to say you feel fifty things at once.

That we must not rely on small children to crush their emotional reality into tidy categories—just to protect adult comfort.