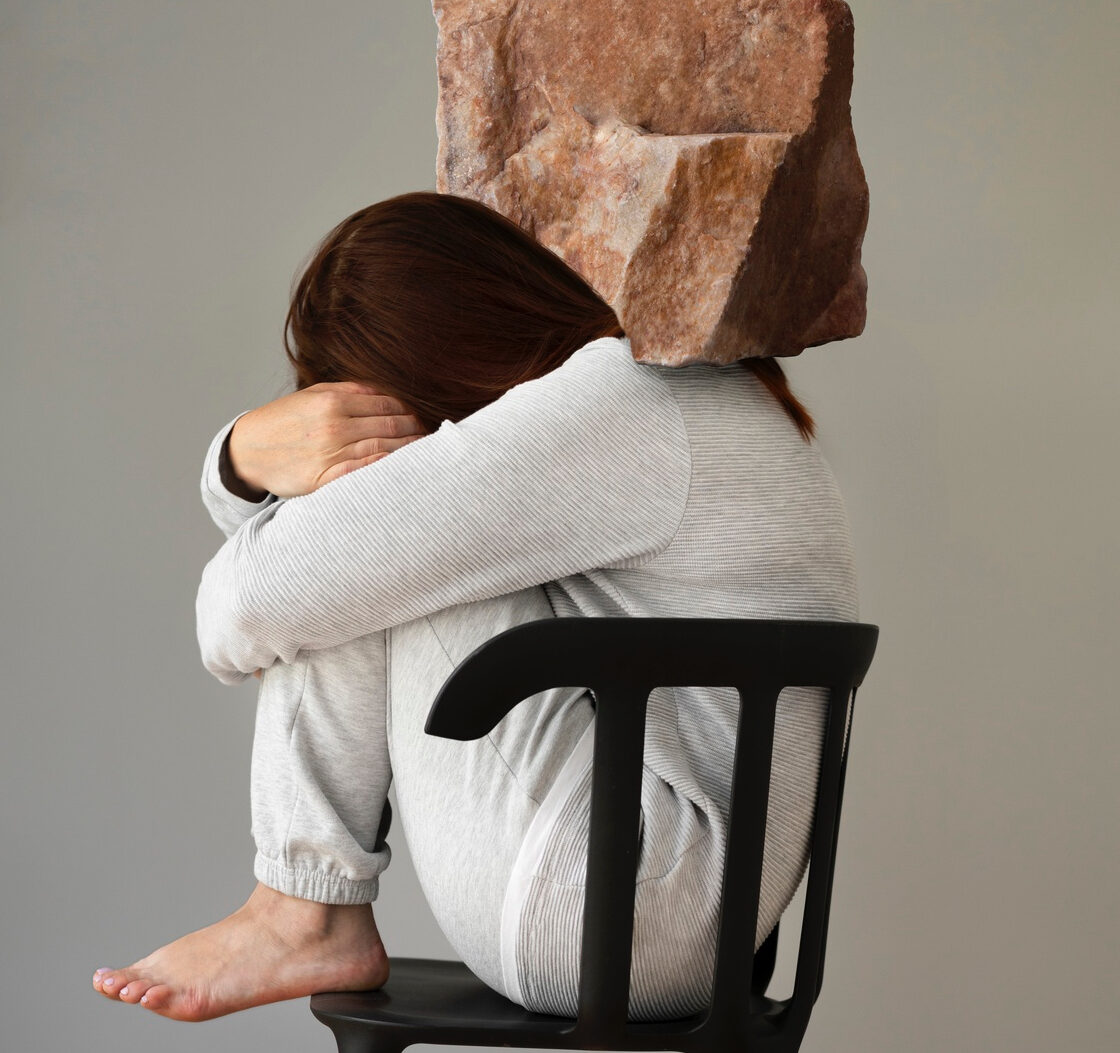

There is a particular cruelty in delayed care, of watching a child falter for weeks or months while teams gather data, debate thresholds, and cite process. It is the cruelty of waiting for collapse before responding, of constructing intervention around crisis instead of prevention. And when the child finally does break, when their distress spills over into public disruption—only then does the system move. But by then, the damage has already taken root.

For many children, this is the only pathway to being seen: fall apart. Become disruptive. Frighten someone. Force the system’s hand.

-

Maybe tomorrow: reflections on goal post shifting and the economics of access

There were accommodations on paper and endless lip-service meetings. But none of it happened in the classroom. And every time we did what was asked—another intake, another…

The invisible cost of waiting

In the early stages of a child’s distress, support teams often take a ‘wait and see’ approach. They observe, document, and speculate. They reassure parents with language that sounds collaborative—“We’re monitoring,” “We’ll see how things evolve,” “Let’s touch base next month”—but this delay does not happen in neutral time. The child is deteriorating. Their nervous system is already taxed. They are denied access to safety during critical periods of learning. And yet the absence of overt disruption is taken as evidence of coping.

By the time support is offered, the child is often in crisis. What could have been addressed with relationship-building and minor adjustments is now a complex, risk-coded emergency. And because the system waited until the child broke, the child’s collapse becomes the justification for more invasive measures: isolation, shortened days, one-to-one aides who shadow them like guards. The original harm disappears from view. The child becomes the problem.

Institutions have an appallingly short memory

September arrives and everything resets—new teacher, new classroom, new goals—and suddenly your child is expected to be a clean slate, as if the harm inflicted the year before was erased with the filing of the last report card. In January, again. After March break, again. Whatever rupture came before is treated as irrelevant, resolved, or imagined. And whatever dysregulation or refusal your child carries in their body—the grief, the vigilance, the shutdown—is no longer seen as a response to what they endured. It is seen as a feature of who they are. Their body tells the truth, but the institution calls it pathology. The system forgets what it did, but it never forgets how to blame the child for surviving.

Refusal reframed as threat

For children with profiles like my son’s—those whose disabilities are ambiguous, masked, or relational—the threshold for support is not need. It is disruption. They must prove themselves in crisis. They must earn help by becoming intolerable. If you try to strangle your teacher in kindergarten, you might get a few months of support. If you fall and come up swinging, if you collapse so publicly, if tear the classroom apart—then maybe, just maybe, someone will call a team meeting. Maybe someone will offer help. But by then, your nervous system is wrecked. By then, the trust is gone. By then, what they’re offering might not help.

Once a child has reached that crisis point, support is no longer offered as care. It is offered as a form of behavioural containment. The unspoken message becomes clear: comply with this new plan or risk further exclusion. Accept these interventions—often designed without your input—or face suspension, relocation, or placement in a special setting.

And when the support finally comes, it’s dressed up as a behaviour plan. A safety plan. A sticker chart. A checklist of “expected behaviours” and “replacement strategies.” A menu of special interests you’re allowed to access if you’re good—if you comply, if you mask, if you hold it together long enough to be useful to the system again. The care is conditional, rationed, steeped in euphemisms. And every piece of it says the same thing: your right to regulation, joy, or interest is contingent on your ability to perform wellness.

By waiting for collapse, schools create the very emergency that justifies coercive response.

And when families push back—when we say the child needs rest, not management, when we decline tokenistic or surveillance-based “supports”—we are often framed as uncooperative. But what we are refusing is care that arrives too late and in the wrong form. What we are refusing is punishment repackaged as help.

-

Poise as pedagogy

There is a cost to composure that institutions never count. When schools reward mothers for staying calm in the face of harm, they turn grace into a gatekeeping tool and punish those who dare to grieve out loud.

Collapse as currency

The system responds to what it can quantify. It tracks absences, office referrals, incident reports. It does not track despair. It does not record masking or internalised shame. It does not measure the harm of being misunderstood, under-supported, or persistently surveilled.

In this context, collapse becomes currency. A child’s right to support must be purchased with suffering. Families must prove the depth of harm to unlock even minimal accommodations. And once support is offered, it is often conditional, framed as remediation rather than relational repair. If the child cannot meet behavioural expectations, the support is withdrawn or the placement revoked.

This cycle teaches children and families that help is only available when harm is already done.

-

Apparently, starving yourself isn’t a serious mental health condition in VSB

There is a kind of harm that unfolds slowly — a hunger that accumulates across weeks…

Debility by design

Jasbir Puar’s concept of debility is crucial here. She defines it as the slow, systemic grinding down of bodies and capacities through structural neglect and exposure. In contrast to disability—which is often medicalised, codified, and sometimes accommodated—debility is ambient and unacknowledged. It is what happens when the system denies care until a child disintegrates, then treats that disintegration as personal failure.

My son lives in this space. Although he has many formal diagnoses, his intelligence has precluded the education system from believing or appropriately accommodating any of them. Distress is planned, misnamed, or diminished until it becomes uncontainable. And then, instead of being supported, they are managed. Instead of being protected, they are pathologised. And once they are too big, too loud, or too angry, they are removed entirely.

This is debility. And that is how the BC public school system is designed.

A call for structural repair, not reactive response

Crisis response is necessary when harm escalates—but it should never be the only form of care the system provides. Children should not have to fall apart to be taken seriously. And families should not be forced into grateful compliance when care finally arrives too late to heal.

Real support is built in advance. It is a bridge, not a destination you get to through crawling through glass. It is designed in relationship. It is given unconditionally. It honours refusal and understands collapse not as threat, but as truth.

Until schools shift from crisis-based response to preventive, relational care, they will continue to coerce children into collapse and kids will keep being disappeared.

-

What would it really cost to fix the problem?

We talk so much about the cost of inclusion—as if it’s indulgent, optional, something that must…