Some days I feel my own face harden, the jaw locking and the air leaving my lungs in a clipped exhale, the eyes narrowing into a refusal that feels like muscle memory. It is the same recoil I have seen across the meeting table, the same signal that too much has been brought into the room. Advocacy has trained me to notice it in others; now I feel it in myself and know the weight it carries. It’s the body’s reaction when input feels like a threat to survival.

It comes when my child’s need collides with the thin edge of my capacity, when their urgency presses into my skin and my body turns away. The sensation is sharp and immediate, a current that moves through muscle and breath before thought can catch it.

Poise—the composure I have performed to survive rooms that punish visible distress—has a shadow. The longer I have held that mask for the sake of credibility, the more it calcifies and I feel paralysed in place.

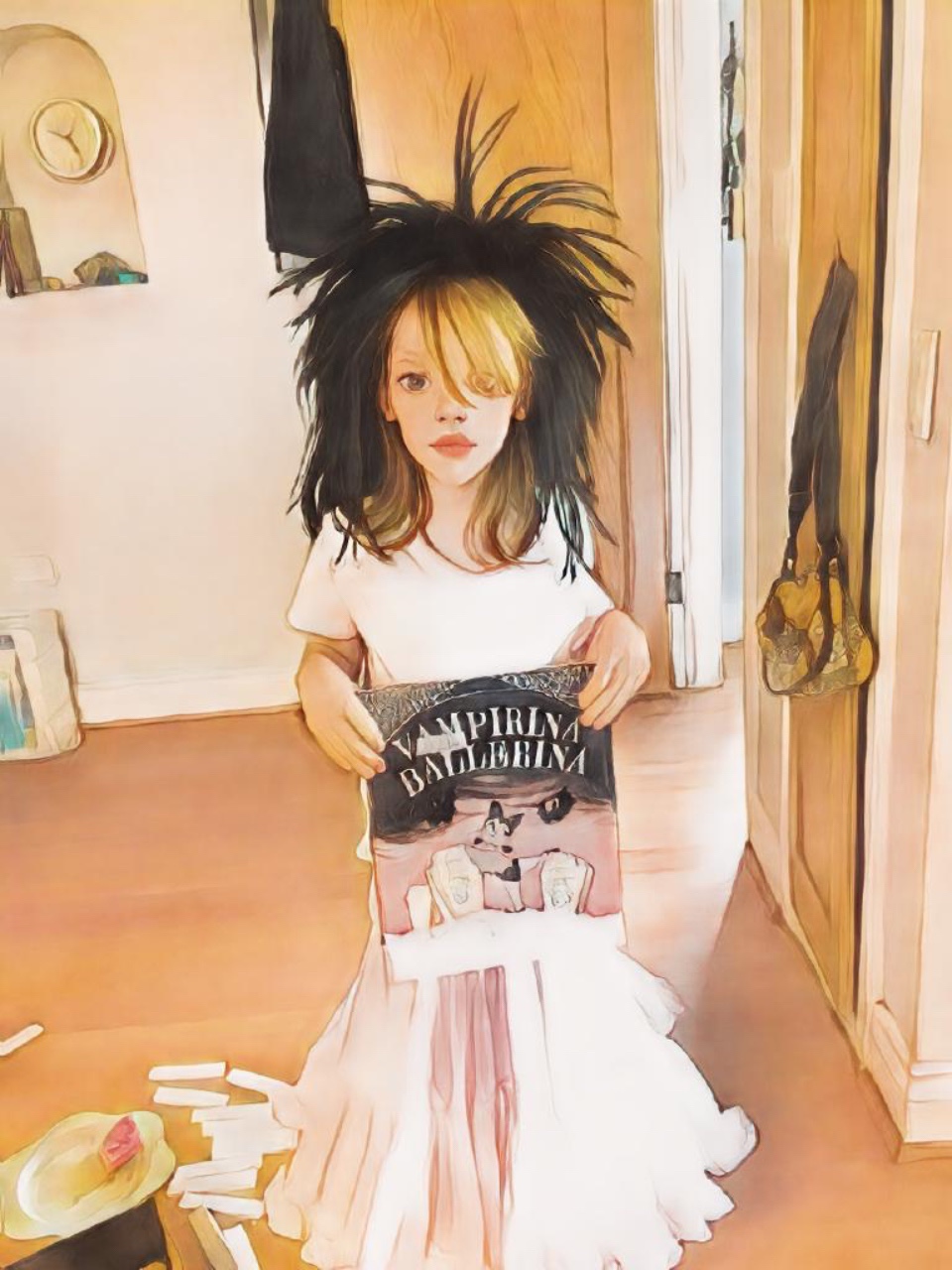

I begin to detest myself, unwilling to live yet unwilling to abandon my children, holding the two like live wires in my hands. I feel pathetic, beyond redemption for how badly I believe I have failed. I believe my ex-husband when he calls me a bad mom, taking on the role of aberration as though it were the only truth available. I stand smiling for my children, trying to give them what I think they need to grow into strength and confidence, to keep them from feeling the rot that is spreading through me.

-

Poise as pedagogy

There is a cost to composure that institutions never count. When schools reward mothers for staying calm in the face of harm, they turn grace into a…

The fracture between survival and self

Kindergarten reduced me to a triage list: feed the children, keep the job, keep the public rooms intact, wash the dishes, attend the meetings, try to be good. Every other part of living fell away without ceremony, until the absence of reading, movement, friendship, and rest became so total that I could no longer name what had gone missing. I had to witness my own reality in silence; I disassociated, depersonalised, and I clung to fragments of safety until the pandemic split that fracture wide, replacing solo hours with interruptions, meltdowns, and a sealed-loop tension.

I found myself living the double-bind I had named in others: composed enough to function, fractured enough to know the cost. I would sit in video calls with a steady voice while chaos crashed in the other room, my heart breaking, and when the day ended, I was inconsolable and irate. The gap between appearance and reality became a gulf that consumed energy I could no longer spare.

Disappointment in my own promise of protection

Motherhood was supposed to mean that I could shield my children from harm, or at the very least intervene before harm became entrenched. The work of advocacy has exposed the brittleness of that promise. Each meeting where harm is denied, each refusal to provide support, each polite dismissal chips at the core expectation I once had of myself: that my vigilance and my voice would be enough. The disappointment is not abstract; it is cellular, a corrosion that eats into my sense of purpose, leaving me to wonder whether my children will remember me as the mother who fought for them or as the mother who failed to keep them safe.

-

On masking and self regulation

One of the most surprising and disorienting lessons I’ve learned—through parenting neurodivergent twins, through surviving the school system alongside them, and through slowly unmasking myself—was this: You can’t fake regulation You cannot breathe slowly enough, sit still enough, or smile warmly enough to…

Masking from myself

The ADHD medication stripped away the haze and revealed how fully I had trained my body to endure: wool that burned against my skin because I had been told it meant care, bedtime snuggles that raised hives because discomfort was supposed to be ignored, hours in overheated rooms because endurance was equated with virtue. I recognised in my own body the same violences I had seen schools demand from children—especially girls—who learn that calm earns safety and visible need is shameful.

These children, like me, become adept at preempting the reactions of others, smoothing over every sign of distress before it can invite scrutiny. They learn to frame their pain as politeness, their withdrawal as resilience. I realised I had been modelling for my children the same self-erasure I wished to protect them from, and that recognition landed with both grief and urgency.

The disgust of hyper-empathy

When my children recount their stories—the reasons they believe they were left out, punished, or made to feel lesser—I feel those narratives in my body with unbearable clarity. I hear their justifications, their attempts to make sense of neglect, and I know exactly how they learned to bend the truth inward. This hyper-empathy, once a point of pride, now feeds my self-disgust, because I see my own role in sustaining the conditions that shaped those stories. I can feel the contours of their shame as if it were my own skin, and with it comes the guilt of having been both their fiercest advocate and an unwilling participant in the harm.

-

Disgusted by my advocacy

I have become hyper-attuned to the particular curl of a staff member’s lip, the slight recoil in their chair, the clenched tone when I insist—again—that my child…

Shame as the system’s most efficient export

I have written about how the sighs, the narrowed eyes, the watch-your-tone stare tell my children they are ungrievable. I carry that home, unbox it, and teach it to myself until it becomes the lens I see through. This is how the system’s demand for poise works: it makes distress the problem of the distressed, recasting moral injury as personal failing.

Poise as pedagogy protects the institution by ensuring that visible suffering is always suspect, never situational. It allows the harm to remain unexamined while the harmed person becomes both subject and enforcer, training themselves to meet cruelty with composure and calling that composure strength.

Double edged sword

Self-respect and self-disgust now live close enough to share a pulse. I fight the institution with every fibre, yet I turn that same edge inward without hesitation. When you externalise, the world cuts you down. When you mask, you are the knife. I know how to keep my voice even, my tone measured, my face steady even as my body thrums with rage. The car becomes my confessional, the wipers keeping time as I circle the same question: how to hold my children’s worth, and my own, in a system that demands I bury both beneath composure.

How the system benefits from this

The truth is that my self-disgust is not a side effect—it is the purpose of the system. A caregiver who doubts herself is easier to dismiss, easier to control, easier to overload with the invisible labour that keeps the machinery turning without challenging its design. This is the compliance economy in practice: extracting emotional and procedural labour from those already harmed, punishing clarity as aggression, rewarding silence as virtue. The harm done to my children is mirrored in the harm done to my own sense of self, and both serve to contain risk for the institution.

When caregivers are bent inward by shame, they are less likely to organise, to demand resources, to force budgets to reflect reality. Devaluing our voices deflects cost and protects he reputation of those in power. It keeps risk at arm’s length from the board table, the ministry office, the executive suite.

This is the political economy of care under austerity: women’s unpaid, uncredited labour absorbing the shocks of institutional neglect, our bodies and reputations treated as expendable buffers for public systems designed to spend as little as possible on the people who need the most.

This is structural: a gendered and ableist extraction of emotional and physical resources, legitimised through cultural narratives that frame endurance as moral worth. This is care as exploitation, resilience as currency, and composure as a tool of governance. Until it is named as intentional design rather than collateral damage, the cycle will continue, profitable for those who never have to bear its true costs.

-

The compliance economy

In their article Of Sinners and Scapegoats: The Economics of Collective Punishment, J. Shahar Dillbary and Thomas J. Miceli argue that collective punishment emerges not merely as a failure of precision or fairness, but as a deliberate mechanism for preserving internal group cohesion. The…