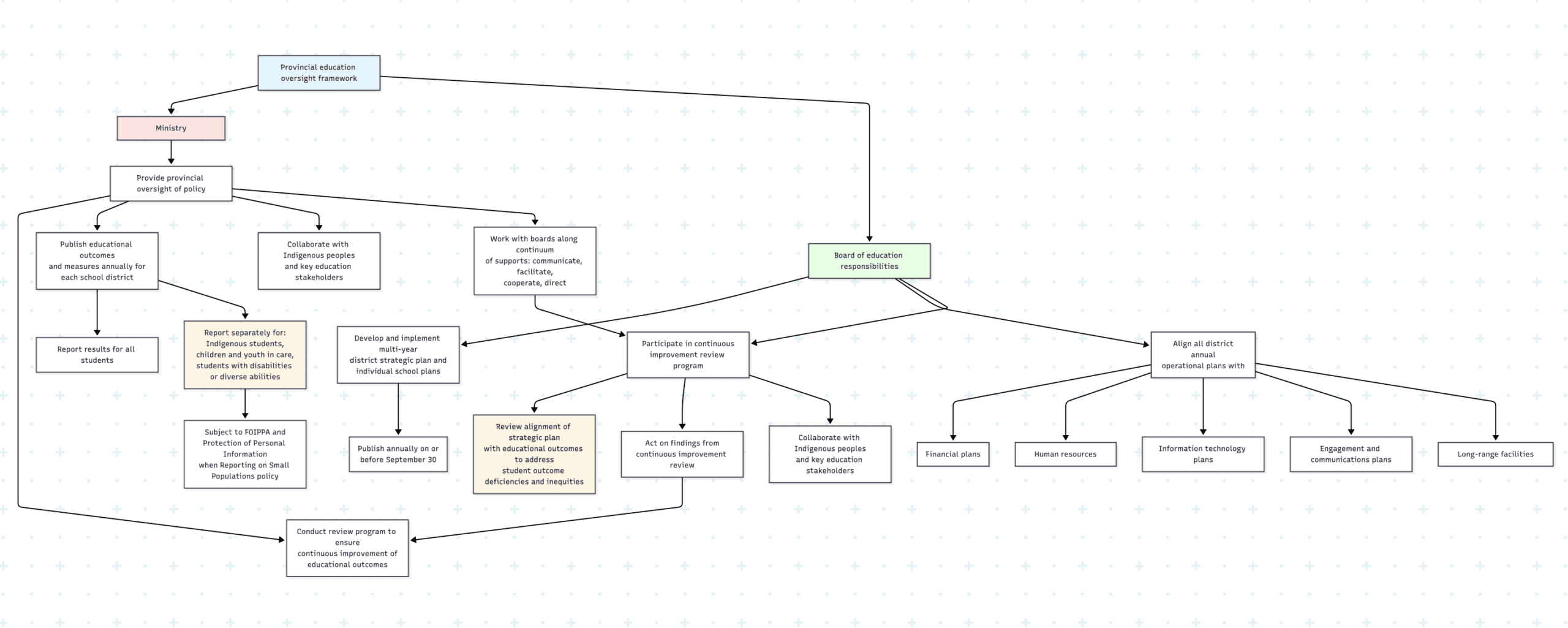

In 2020, the British Columbia Ministry of Education and Child Care brought into force the Framework for Enhancing Student Learning, a policy architecture ostensibly designed to guide the province’s approach to continuous improvement in public education, with particular attention to improving equity for Indigenous students, children and youth in care, and students with disabilities or diverse abilities. The Framework consists of two components: the Framework for Enhancing Student Learning Policy, which outlines responsibilities for the ministry and school boards, and the Enhancing Student Learning Reporting Order, which requires districts to publicly report on specific student learning outcomes each year.

Executive summary

- No enforceable standards: The Framework mandates continuous improvement without defining what improvement looks like, establishing measurable targets, or creating timely consequences for district failure.

- Resource evasion: Districts report extensively on outcomes but receive no dedicated funding for improvement work, forcing them to reallocate existing inadequate resources while narrating this reallocation as “strategic alignment.”

- Data architecture designed to hide exclusion: Districts must report academic outcomes but face no requirement to track or report exclusionary practices—room clears, restraints, partial schedules, chronic absence by designation, or accommodation denials.

- Delay as governance strategy: Reporting timelines, enforcement mechanisms, and strategic planning cycles operate on schedules mismatched to the urgency of student harm, converting crisis into patient iterative process.

- Compliant failure by design: Districts can follow every Framework requirement while continuing to exclude disabled children because the Framework asks districts to self-assess effectiveness, permits indefinite strategic pivoting, and establishes no minimum standards for what constitutes adequate service.

Introduction

The Framework’s stated commitments feel ambitious in their scope—system-wide alignment, evidence-informed decision making, collaborative engagement with Indigenous peoples and education partners, targeted capacity building, and continuous improvement cycles designed to close persistent outcome gaps for marginalized student populations. The architecture presents itself as rigorous, data-driven, and equity-focused, deploying the language of contemporary public sector reform: strategic planning, outcome measures, iterative review, stakeholder engagement, and tiered support systems.

“Boards of education will set, create and maintain a strategic plan, annually report on student outcomes and put systems in place to continuously improve the educational outcomes for all students and improve equity for Indigenous students, children and youth in care, and students with disabilities or diverse abilities.”

Framework for Enhancing Student Learning

The Ministry establishes a continuous improvement framework requiring boards to publish disaggregated outcome data for vulnerable student populations—including disabled students—and participate in annual strategic planning reviews, while retaining authority to escalate intervention from collaborative support through to ministerial directives or appointment of official trustees when boards fail to meet School Act obligations; however, the framework defines accountability exclusively through planning compliance and outcome measurement rather than through prohibitions on exclusionary discipline, meaning boards can satisfy all reporting requirements while continuing to use room clears, partial schedules, and coercive safety plans without consequence, because the system measures administrative process rather than substantive harm, allowing the state to seize control of boards for paperwork failures while leaving the exclusion of disabled children entirely outside the enforcement architecture.

I mean, it sounds better than nothing right?

The plan says “The Ministry will work with Boards of Education to build capacity along a continuum of needs,” including:

Communicate

Share best practices and support boards in meeting provincial goals

Facilitate

Create peer review teams to build capacity based on identified gaps

Cooperate

Provide intensive support, training, and action planning for struggling districts

Direct

Issue ministerial directives or appoint official trustees to replace elected boards

Essentially, the Framework creates an elaborate accountability system with powers to dissolve elected boards for administrative failures or poor test scores, yet nowhere prohibits the exclusionary practices—room clears, partial schedules, safety plans—that produce those outcomes, making this worse than nothing because it manufactures the appearance of rigorous equity oversight while systematically protecting the disciplinary regime that harms disabled children.

And, the architecture reveals itself through what it refuses to build as much as through what it constructs. When examined closely, the Framework operates as performance management infrastructure without performance standards.

It produces the aesthetic of accountability while systematically evading the transparency, enforcement, and resource commitment that genuine accountability would require.

Just a Parent

It asks districts to continuously improve student outcomes while refusing to measure the exclusionary practices that produce inequitable outcomes in the first place, mandates reporting without funding the capacity to respond to what the reports reveal, and promises oversight without establishing consequences for districts that fail to improve or actively harm the students the Framework purports to protect.

This paper

This paper examines the Framework through the analytical lens of someone who has experienced its operations from multiple positions simultaneously: as the mother of two AuDHD children who have been harmed by the exclusionary practices in BC schools; as a solution architect who builds digital systems and understands how data architectures encode political choices; as an accessibility design specialist who recognises when inclusion rhetoric masks structural violence; and as an advocate who has spent years documenting how BC schools use room clears, partial schedules, informal exclusions, and “safety plans” to systematically remove disabled children from public education while maintaining the appearance of compliance with inclusion policy.

What follows is a detailed analysis of how the Framework constructs accountability without adequacy, measurement without visibility, and improvement rhetoric without the material conditions—funding, enforcement, data transparency, or ambitious targets—that would make improvement possible for the children currently experiencing harm.

What the Framework claims to do

The Framework for Enhancing Student Learning presents itself as a comprehensive system designed to ensure that “all learners” in British Columbia’s public education system receive the supports necessary to develop their “intellectual, human and social and career development.” It directs districts to focus on continuously improving educational outcomes for all students, with particular attention to three priority populations: Indigenous students, children and youth in care, and students with disabilities or diverse abilities.

The policy establishes a clear division of responsibilities between the ministry and school boards. Districts must develop multi-year strategic plans focused on student learning outcomes, align all operational planning—financial, human resources, facilities, communications—with these strategic priorities, and publish annual reports that include visualizations of required provincial data measures alongside analysis of how effectively the district is serving priority student populations. The ministry, in turn, commits to publishing outcome data annually for all districts, reviewing district reports through expert teams, and providing capacity-building supports along a continuum that ranges from “communicate” (sharing promising practices) to “direct” (issuing administrative directives under the School Act when boards fail to meet obligations).

The Framework’s language emphasises collaboration, evidence-informed decision making, and iterative improvement cycles. It requires districts to engage meaningfully with Indigenous communities, students, families, and education partners when developing strategic priorities. It mandates that districts analyze outcome gaps, implement targeted strategies to address inequities, and report publicly on progress and challenges. The ministry’s Continuous Improvement Program is described as bringing the Framework into practice through four interconnected elements: collaborate with education partners, publish results to inform district planning, review reports to assess system progress and identify supports needed, and build capacity through targeted resources.

The Framework grounds itself in commitments to reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, alignment with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and the province’s obligations under the BC Tripartite Education Agreement. It acknowledges the importance of the Statement of Education Policy Order’s definition of the “Educated Citizen” and commits to supporting the intellectual, human, social, and career development of every student. Districts are directed to ensure their goals are “specific, meaningful, measurable, and evidence informed,” with a focus on understanding evidence and developing actions to improve student outcomes.

This is the Framework’s self-presentation: a robust, equity-focused, collaborative approach to system-wide improvement that centres student learning, respects Indigenous sovereignty in education, and builds district capacity to serve historically marginalised populations more effectively.

-

VSB’s accessibility plan: more marketing than meaningful change

The Vancouver School Board has released its Accessibility Plan for 2025–2028, a document that positions itself as a forward-looking commitment to equity, belonging, and barrier removal, offering warm assurances about inclusion while presenting a polished institutional narrative that feels carefully tuned for public…

What the Framework actually does: procedural compliance without protective enforcement

The gap between the Framework’s stated intentions and its operational architecture becomes visible the moment you search the policy documents for the mechanisms through which these intentions would be realised. The Framework constructs an elaborate apparatus for planning, reporting, reviewing, and supporting—but it systematically avoids establishing enforceable standards, measurable targets, dedicated funding, or timely consequences for districts that continue to harm the students the Framework purports to protect.

The enforcement problem: consequences deferred indefinitely

The word “enforcement” appears exactly zero times in the Framework policy. The word “consequences” appears once in the accompanying Q&A document—in the context of masking data to avoid them. The word “rights” appears three times, always in phrases referencing external documents (Human Rights Tribunal, Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples), never as an assertion of what children are entitled to receive or what districts are obligated to provide.

What you will find instead: an iterative support continuum described as communicate, facilitate, cooperate, and direct. Only at the extreme end of this continuum—”direct”—does anything resembling enforceability appear, and even then it is framed as ministerial discretion exercised in response to a board “failing to meet its obligations under the School Act” or when “it is in the public interest to do so.” These are procedural standards and political determinations, not automatic triggers tied to measurable student harm.

The practical effect of this architecture: a district can operate partial schedules that remove disabled children from school for hours or days each week, deploy room clears as routine discipline rather than emergency safety interventions, fail to develop or implement IEPs, repeatedly exclude the same children through informal “parent-requested” absences, and report persistently poor outcomes for students with disabilities year after year—and the prescribed ministerial response is renewed “capacity building,” not intervention, investigation, or remedy.

The Framework treats district failure as a support deficit rather than a rights violation. It assumes that outcome gaps persist because districts lack knowledge, resources, or planning capacity—not because districts are actively choosing exclusionary practices that are cheaper and easier than providing genuine accommodation and inclusion. This assumption forecloses the possibility that some districts are not trying and failing to include disabled children, but rather succeeding at excluding them because exclusion solves the resource scarcity problem in ways that inclusion does not.

It’s almost like they think the plan is magic!

The ambition problem: continuous improvement without defined improvement

Strategic planning frameworks genuinely pursuing transformation establish specific, measurable, time-bound targets—Big Hairy Audacious Goals (BHAGs) that name the gap between current harm and desired change in concrete terms, then track progress toward closing that gap through accountability mechanisms with teeth.

This Framework sets zero targets: no reduction percentages for exclusion rates, no timelines for eliminating partial schedules, no benchmarks for decreasing room clears, no concrete commitments to close outcome gaps for disabled students by specific dates or margins—making this a system designed to measure harm perpetually without ever committing to its cessation, because targets would create accountability for actual change rather than endless documentation of the status quo.

The word “target” appears nowhere in the policy; the word “goal” appears only in the context of districts setting their own goals through strategic planning, never as provincial standards establishing what improvement must look like in measurable terms—you will not find language like “outcome gaps between disabled students and their peers must narrow by X% within Y years” or “no district may operate above Z% of its disabled student population on partial schedules.”

Without targets, the system cannot fail: boards can demonstrate “continuous improvement” through marginal changes while outcome gaps widen, children graduate through modified programming that forecloses futures, and districts claim progress by reporting the survival rate of children who endured exclusion rather than evidence the system itself has changed.

This converts urgency into process, stretching present suffering across endless cycles of planning, reporting, and capacity building that proceed indefinitely without reaching the children experiencing harm right now—preserving status quo operations under the aesthetic of reform, performing accountability without risking failure, celebrating measurement sophistication while refusing to commit to measurable reduction in the violence being measured.

The funding problem: mandates without money

The Framework imposes significant new procedural obligations on school districts: multi-year strategic planning centred on student learning outcomes, annual reporting with data visualisation and analysis, meaningful engagement with Indigenous communities and education partners, review and adaptation cycles, and alignment of all operational plans with strategic priorities. These obligations require staff time, expertise, and coordination—none of which the Framework funds.

What the Framework does instead: it mandates that districts “align all district annual operational plans, including but not limited to financial plans” with Framework objectives. This is budget ventriloquism—forcing districts to narrate their existing spending as if it were already designed to serve Framework goals, regardless of whether current resources are adequate to achieve those goals.

The Q&A document confirms this explicitly: “The FESL’s budget is not a separate line item but is the portion of the school district’s total operational budget that is dedicated to the strategies and goals outlined in the FESL.” Translation: districts must reallocate existing funds to demonstrate Framework alignment. This means spreading staff capacity thinner to accommodate additional reporting and planning requirements, or pulling resources from other areas to create the appearance of Framework-directed investment, or both.

The Framework creates new accountability infrastructure—report review teams, evaluation criteria, capacity-building programs, data dashboards—but the burden of producing the reports, analyzing the data, convening the engagement processes, and implementing the “targeted strategies” falls to districts operating within funding envelopes that have not expanded to accommodate this work. The ministry will “facilitate,” “communicate,” “cooperate,” and in extreme cases “direct”—but it will not fund.

This is austerity architecture disguised as continuous improvement. The state demands better outcomes while maintaining the resource scarcity that produces poor outcomes in the first place. Consider what genuine improvement for disabled students would require: hiring additional educational assistants and learning support teachers, reducing class sizes, providing intensive professional development on neurodiversity-affirming practices, increasing psychological assessment capacity to reduce wait times, implementing evidence-based interventions, and possibly redesigning physical spaces to accommodate sensory and physical access needs. None of this is cheap, and none of it appears in a budget line called “Framework implementation.”

Instead, districts are asked to demonstrate that their existing inadequate resources are being “strategically aligned” with improvement goals. This produces a predictable outcome: districts write strategic plans about improving equity while continuing to operate partial schedules for disabled children because they lack the staff to support full inclusion. They visualise data showing persistent outcome gaps while making room clears a routine discipline practice because they haven’t been resourced to build capacity for trauma-informed, disability-affirming approaches. They engage with families about children’s unmet needs, then return to budget meetings where the conversation begins with scarcity, not with what children require.

The Framework asks: “Are you improving?” The materially accurate response would be: “Are you funding improvement?” But that question finds no answer in the policy architecture, because the Framework treats resource adequacy as beyond its scope—an external constraint rather than a prerequisite for the equity it claims to pursue.

Author’s aside: I would prefer to think that the NDP aren’t evil.

To believe that Christy Clark’s BC Liberals didn’t just cut education funding—they installed an entire ideological apparatus inside the machinery of government, people trained in New Public Management thinking who genuinely believe that performance measurement, local accountability, continuous improvement frameworks, and market logic make public services better, and those people are still designing policy even under an NDP government because the NDP can’t afford to lose the institutional knowledge required to operate the system.

So the Framework emerges from machinery still running on libertarian business logic even when nominally serving social democratic political leadership, which is why it produces outputs that look like corporate accountability systems—strategic planning, outcome metrics, tiered interventions, capacity building—rather than outputs that would challenge the foundational premise that schools should exclude disabled children when inclusion costs too much.

The rhetoric of “district accountability” serves that ideological framework perfectly: it decentralises responsibility so the province never has to confront whether the system itself is structurally designed to fail disabled children, never has to acknowledge that scarcity is engineered rather than natural, never has to commit provincial resources to make inclusion possible—instead, districts get measured on outcomes produced by inadequate funding, then blamed for deficiencies, then subjected to capacity building interventions that teach them to manage scarcity more efficiently rather than challenging scarcity itself.

The NDP politicians might be genuinely committed to equity, but they’re operating machinery built by people who believe public services should operate like businesses, and that machinery keeps producing business solutions—performance management, accountability frameworks, continuous improvement—when what’s needed is acknowledgment that the system is fundamentally fucked and requires transformation, not optimisation.

You can’t fix institutionalised exclusion with continuous improvement cycles when the people designing those cycles believe the system works and just a wee adjustment.

How the Framework manages scarcity rather than challenges it

The Framework’s funding evasion is structural, designed to preserve provincial fiscal constraints while producing the appearance of equity commitment. This becomes visible when examined alongside BC’s broader education funding architecture, which has failed to keep pace with known needs—inflation, enrolment growth, and rising costs of serving students with complex needs.

The ministry knows what genuine inclusion requires: adequate educational assistant staffing, reduced class sizes, intensive professional development, expanded assessment capacity, specialised supports. The ministry also knows that BC districts already operate under manufactured scarcity, forced to choose between competing needs because baseline funding does not cover the actual cost of meeting legal obligations to disabled students.

The Framework is designed to operate within this scarcity without challenging it. By requiring districts to “align operational plans including financial plans” with Framework goals rather than providing dedicated improvement funding, the Framework forces “budget ventriloquism”—districts must narrate existing inadequate spending as if it were already strategically designed to close equity gaps. Districts must demonstrate current resources are being used effectively before claiming additional support is needed, even though current resources are demonstrably inadequate to achieve the outcomes the Framework demands.

This creates a double bind: districts cannot improve outcomes without additional resources, but the Framework provides no additional resources and asks districts to prove they are using existing resources well by…improving outcomes. The Framework resolves this bind by converting it to process—when outcomes remain poor despite strategic efforts, the response is more planning, more capacity building, more iterative adjustment. Never direct confrontation with resource inadequacy as the barrier to improvement.

Lemme put it another way: it’s fucking fucked!

The Framework as austerity management tool allows the province to:

- Acknowledge persistent outcome gaps (demonstrating awareness and concern)

- Require districts address gaps through strategic planning (demonstrating commitment to improvement)

- Provide technical support and capacity building (demonstrating provincial engagement)

- Avoid funding the material conditions that would make improvement possible (preserving fiscal constraints)

- Position continued poor outcomes as district implementation problems rather than provincial funding failures (deflecting accountability upward)

The Framework does not ask: “What would adequately serving disabled students actually cost, and is the province funding that?” Instead it asks: “How can districts better use existing resources to improve outcomes?” This framing treats resource adequacy as external to the Framework’s scope, even though resource inadequacy is arguably the primary barrier to the equity the Framework purports to advance.

The result: disabled children experience exclusion not because districts are incompetent or malicious, but because exclusion is cheaper than inclusion, and the Framework provides no mechanism forcing the province to fund inclusion adequately while providing elaborate mechanisms through which districts can be held accountable for failing to achieve equity on an austerity budget.

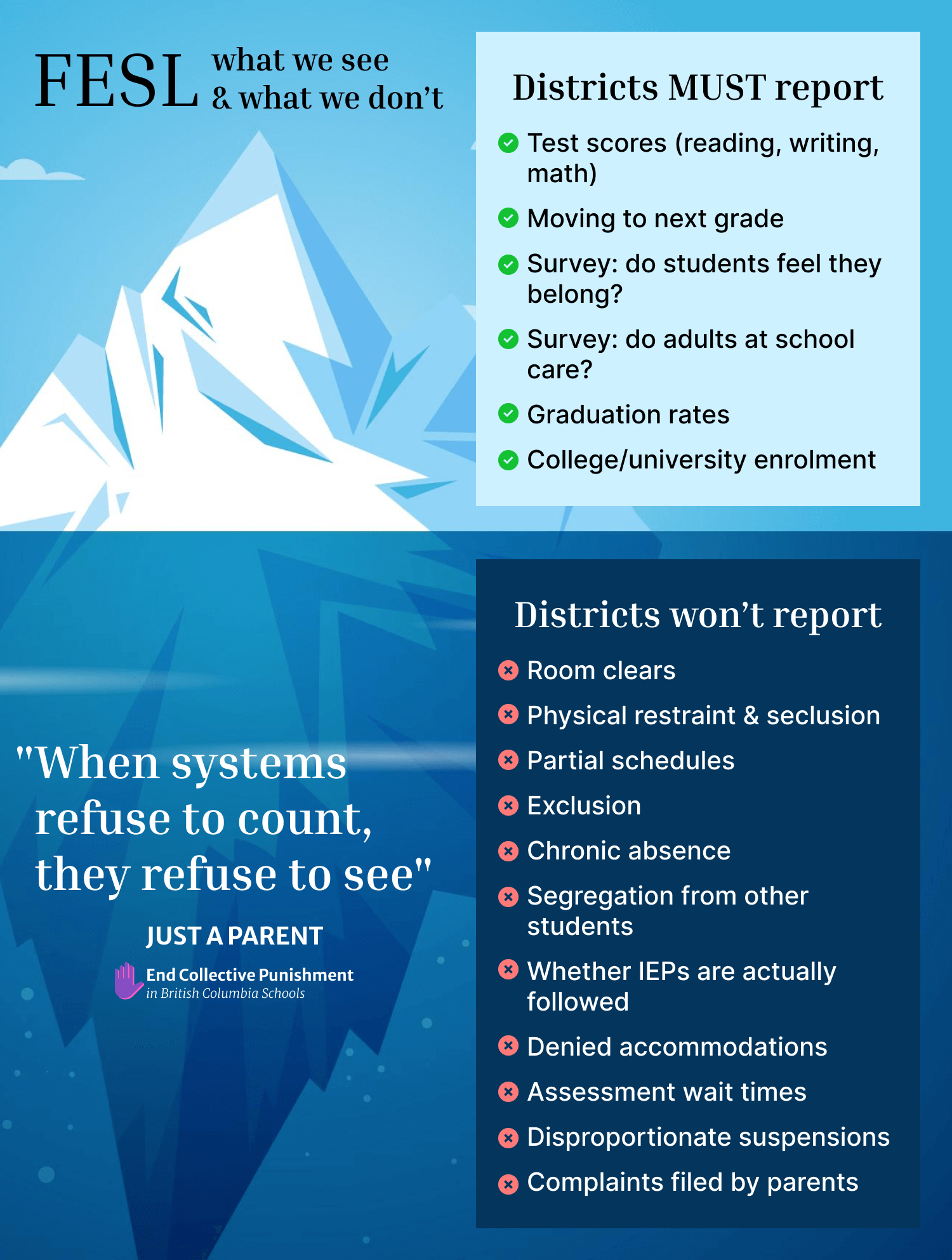

The data architecture problem: measuring outcomes while hiding exclusion

The Framework’s most significant structural evasion operates through its data requirements. What the Framework asks districts to measure and report reveals what the system values; what it leaves unmeasured reveals what the system prefers to ignore.

What districts must report

For all students and separately for each priority population (Indigenous students, children and youth in care, students with disabilities or diverse abilities), districts must report:

- Foundation Skills Assessment (FSA) scores in literacy and numeracy

- Student Learning Survey results (belonging, safety, engagement)

- Grade-to-grade transition rates

- Graduation assessment results

- Six-year completion rates

- Post-secondary institution transition rates

These are outcome measures—they tell you how students performed academically, whether they graduated, and whether they transitioned to post-secondary education. They are the measures that allow districts to demonstrate “progress” when scores inch upward or completion rates improve marginally. They are also measures that disabled students frequently perform poorly on, producing data that districts can use to justify arguments that these students are “not capable of” grade-level curriculum, that they “need” modified programming, that outcome gaps reflect “inherent limitations” rather than systemic failure to accommodate.

What districts are not required to report

The Framework requires no reporting whatsoever on exclusionary practices or access to education. Districts are not asked to track, analyze, or publicly report:

- Attendance rates by designation

- Chronic absence rates by designation

- Formal suspension and expulsion rates by designation

- Informal exclusion rates (sent home early, kept home by parent request, partial schedules) by designation

- Room clear incidents by designation

- Physical restraint incidents by designation

- Seclusion incidents by designation

- Time spent in general education vs. segregated settings by designation

- IEP development and implementation rates (the Framework requires reporting on development but not on whether developed IEPs are actually implemented)

- Wait times for psychoeducational assessment by suspected disability category

- Proportion of students on modified vs. adapted programming

- Accommodations requested, provided, and refused

- Human Rights complaints filed related to disability discrimination

- Family advocacy patterns (how many families had to hire advocates, file complaints, or pursue tribunal processes to access appropriate education)

This is not an oversight. This is the Framework’s foundational evasion: it measures the outcomes of exclusion while refusing to measure exclusion itself.

Consider what this data architecture makes invisible: my autistic son was placed on a partial schedule in Grade 1, attending only three hours daily in what the district framed as “building his capacity” for full-time attendance. This partial schedule does not appear anywhere in the Framework’s required reporting. His chronic absence became statistically invisible. His exclusion from a full year of Grade 1 curriculum was reframed as accommodation rather than access deprivation. When he struggled academically in subsequent years, those outcome gaps would be attributed to his disability rather than to the year of education the district denied him. The Framework would eventually count him in transition and graduation data, measuring his achievement after exclusion without ever measuring the exclusion that shaped what achievement was possible.

This is not a flaw in the Framework’s design—the Framework is working exactly as intended. It asks districts to report whether disabled students are graduating, not whether districts are excluding disabled students from the education that would make graduation possible.

If the Framework were designed to make exclusion visible rather than obscure it, district annual reports would include:

- Access measures by designation: How many disabled students attend full-time? How many are on partial schedules? What is the average reduction in instructional hours for students on partial schedules? How many students are in segregated vs. integrated settings? What proportion of the school day do integrated students spend in general education classrooms?

- Exclusion incident tracking: How many room clears occur annually, disaggregated by designation and by individual student? How many students account for the majority of room clears (revealing whether room clears are being used as routine management for specific disabled children)? How many physical restraints and seclusion incidents occur? How long do seclusions last? Who authorizes them?

- Accommodation implementation rates: Not just IEP development, but implementation. How many accommodations listed in IEPs are actually provided? How many accommodation requests are denied? On what grounds? How long do families wait between requesting assessment and receiving assessment?

- Outcome measures by access level: How do academic outcomes differ for disabled students who attend full-time in general education settings versus those on partial schedules versus those in segregated settings? This would reveal whether outcome gaps are produced by “disability” or by denial of access to education.

- Complaint and advocacy measures: How many families file internal complaints each year related to disability accommodation? How many proceed to external processes (Ombudsperson, Human Rights Tribunal)? How much do families spend on private advocacy to access public education? What is the relationship between complaint patterns and outcome improvements?

This data architecture would make visible what the Framework is designed to obscure: that BC districts routinely exclude disabled children from public education through informal mechanisms that operate beneath the threshold of formal discipline statistics, that these exclusions are both cause and consequence of poor academic outcomes, and that what districts report as “outcome gaps” are frequently the predictable results of access gaps the Framework never measures.

What the “Reflect and Adjust Chart” reveals about the Framework’s evasion architecture

The province describes the Reflect and Adjust Chart, which exemplifies how the Framework’s procedural requirements enable compliant failure.

It asks districts to self-assess effectiveness with no external verification:

- “How effectively has this strategy addressed the gap?” – Districts answer their own question

- No requirement to provide actual outcome data supporting their self-assessment

- No independent review of whether their self-assessment is accurate

- No consequences if strategies have been ineffective for years

It allows infinite strategic pivoting without accountability:

- Districts can “discontinue” failed strategies and introduce new ones endlessly

- No requirement to explain why previous strategies failed

- No pattern recognition that if you are constantly discontinuing strategies, perhaps the problem is resource inadequacy not strategy choice

- The “continuous improvement” cycle becomes permission to never actually improve

It enables complete vagueness:

- “What gap or problem of practice does this strategy aim to address?” – Districts can describe gaps in abstract, aspirational language

- “For a specific cohort of students” – No requirement to name which students or demonstrate the strategy actually reached them

- “Based on review of data and evidence” – No requirement to show the data, specify which evidence, or demonstrate the review was rigorous

It explicitly permits districts to ignore their own strategic priorities:

- “If the district’s current Strategic Plan outlines priorities with limited educational focused outcomes, districts teams may choose to complete the chart using the pillars of the Education Citizen”

- Translation: If your strategic plan prioritizes things we don’t like or that would require transparency we’d prefer to avoid, just use these vague categories instead

- This defeats the entire purpose of strategic planning—you don’t get to abandon your stated priorities mid-stream when reporting becomes inconvenient

It produces documentation, not outcomes:

- Filling out this chart is compliance

- Whether disabled children are actually experiencing better education is irrelevant to whether the district has “completed” this process

- The chart itself becomes the deliverable, not improved student outcomes

It has no minimum standards for what constitutes “effectiveness”:

- A strategy that marginally improved outcomes for three students while 47 others continued being excluded could be reported as “effective”

- No requirement to demonstrate statistical significance, sustained improvement, or equity impact

- Districts determine their own success criteria

Delta School District’s 2023-24 FESL report: what compliant failure looks like

Delta’s report matters because it demonstrates what the Framework produces when a district follows all requirements in good faith—a document that creates the appearance of comprehensive transparency while obscuring whether disabled children are actually accessing education. The report is valuable precisely because it demonstrates compliant failure: following all the rules produces a document that looks rigorous while revealing nothing about whether disabled students experience inclusion or exclusion, adequate support or systemic barriers.

The self-assessment circularity

Delta’s report uses the Reflect and Adjust Chart exactly as designed. Look at how this plays out:

For Indigenous student transitions (Grade 10-11 dropped to 89%):

- Gap identified: “This is concerning”

- Strategy effectiveness: They’re “implementing strategies to determine individual students’ context”

- Adjustment: “Collect more anecdotal data”

This is textbook Framework compliance: acknowledge the problem, describe investigating the problem, promise to understand the problem better. What’s missing? Any concrete action with a timeline that would actually change the outcome for students experiencing harm right now.

For post-secondary transitions (Indigenous students dropped from 45% to 26%):

- Gap identified: “An area of concern”

- Strategy effectiveness: “We want to collect data from students within the district to ensure we capture all intended post-secondary plans”

- Adjustment: Better data collection

When the data looks bad, question the data. This is how the Framework’s self-assessment structure enables indefinite deferral—Delta can report they’re “addressing” the problem by investigating it, without ever having to demonstrate they’ve actually improved outcomes.

The vagueness that prevents verification or replication

Look at Delta’s literacy strategies:

K-7 Reading:

- Strategy: “Comprehensive, evidence-supported framework of literacy assessments, resources and classroom routines”

- Effectiveness: “Teachers are reporting that the assessments… are providing them with increased confidence”

- Evidence: “50% of primary teachers are using new measures and early indicators are showing positive impact”

What does any of this mean operationally? Which assessments? What routines? What constitutes “increased confidence”? What are the “early indicators”? How were they measured?

For disabled students specifically, data buried in the appendix shows:

- Grade 1 students with diverse abilities: 28% oral reading fluency, 23% phonics proficient

- Grade 2: 40% oral reading fluency, 30% phonics proficient

These are catastrophically low numbers showing most disabled students aren’t accessing literacy instruction effectively. But Delta’s response in the main report? They’ll “work more closely with administrators and school staffs to assist them in working with and utilising their data.”

This vagueness makes it impossible to know:

- Are these students attending full-time?

- Are they in general education classrooms?

- What specific interventions are they receiving?

- Why aren’t the interventions working?

- What will change?

How can you declare inclusion “the norm” when you don’t measure exclusion rates, room clears, partial schedules, or time in segregated settings? You’ve defined the norm by what you refuse to count. You don’t report modified vs adapted programming rates, which is literally the measure of whether you expect disabled students to meet grade-level standards or have permanently lowered expectations.

And how exactly do you survey students about feeling “deeply engaged and connected” when they’re excluded or on partial schedules? Probably skews your belonging scores when you only ask the kids who survived long enough to still be there.

The data architecture that hides exclusion

Delta’s report is 39 pages with extensive data visualisations. Yet certain data never appears:

Completely absent:

- Room clear incidents (by designation)

- Physical restraint incidents

- Seclusion incidents

- Partial schedule rates

- Chronic absence rates (disaggregated by designation)

- Suspension/expulsion disproportionality

- Time in general ed vs. segregated settings

- IEP implementation rates (they report development, not implementation)

- Accommodation denials

This absence is structural, not Delta’s choice. The Framework doesn’t require this data, so Delta doesn’t report it, so we have no visibility into whether the poor literacy outcomes for disabled students are because:

- They’re not attending school (partial schedules/chronic absence)

- They’re being removed from instruction (room clears)

- They’re in segregated settings where instruction is modified rather than accommodated

- They have IEPs that aren’t being implemented

The resource invisibility problem

The MathMinds section inadvertently reveals how resource scarcity undermines even successful strategies:

Delta reports that schools using MathMinds show better math outcomes than schools not using it. They’ve been rolling out MathMinds for four years. After four years, 18 of 24 elementary schools use it.

Why isn’t it in all 24 schools immediately if they know it works?

The report never answers this directly, but the implication is clear: capacity constraints. They can’t train all teachers simultaneously. They need voluntary adoption. They’re spreading implementation across years.

Meanwhile, children in the six schools without MathMinds continue receiving less effective instruction while Delta gradually expands a program they already know produces better results.

This is the resource problem the Framework renders invisible: knowing what works is not the same as being able to afford to do what works for all children now.

The “concerning” → “investigating” → “adjusting” perpetual cycle

Watch the language pattern throughout Delta’s report when data shows problems:

Indigenous students’ sense of belonging dropped 10-15%:

- “These results are troubling and highlight the need for further investigation”

- No concrete actions, no timeline, no targets

Grade 10-11 transition for Indigenous students at 89%:

- “This is concerning”

- “Strategies are being implemented to determine individual students’ context”

- Translation: we’re going to investigate why students aren’t transitioning, not change what we’re doing to ensure they do transition

Immediate post-secondary transition for Indigenous students dropped to 26%:

- “Area of concern”

- “We want to collect data from students within the district”

- Translation: we think our data collection missed students who had post-secondary plans, rather than accepting that the outcome genuinely worsened

This linguistic pattern—acknowledge, investigate, adjust data collection—creates the appearance of responsiveness while deferring actual intervention indefinitely.

Learn more about Delta School District “diverse abilities” claims with reality checks!

| Topic | Quote from report | Reality check |

| Grade 4 FSA Literacy | “Students with diverse abilities demonstrated a marked improvement in the number of students on track or extending from 35.8% in 2023, to 44.7% in 2024 (52.4% provincial average 2024).” | Despite the framing as “marked improvement,” disabled students remain 7.7 percentage points below their peers (44.7% vs 52.4% provincial average). The report celebrates catching up to systematic underperformance rather than questioning what classroom or assessment conditions produce a 15+ point gap between disabled and non-disabled students. |

| Grade 7 FSA Literacy | “Students with diverse needs showed a mild decline from 42% on track or extending in 2023, to 37% in 2024. This was lower than the provincial rate of 46%” | Disabled students lost ground (dropped 5 percentage points) and are now 9 points below the provincial average and presumably much further below their non-disabled peers in Delta. The report describes this as “mild” and buries the interpretation: “This decline will require further investigation.” No hypothesis offered about whether exclusionary practices, lack of accommodations, or punitive behavioral systems contributed. |

| Grade 10 Literacy Assessment | “For students with diverse abilities in Delta, 65.8% were On Track or Extending, compared to the provincial average of 53.8%.” | While Delta’s disabled students outperform the provincial average by 12 points, the report does not provide the comparison to non-disabled Delta students. The chart shows all resident students at 74% proficient/extending—meaning disabled students are still 8+ points behind their peers, but Delta focuses readers on the provincial comparison to avoid naming local gaps. |

| Grade 12 Literacy Assessment | “Among students with diverse abilities, 75.6% were On Track or Extending, compared to 60.6% provincially.” | Same pattern: Delta celebrates outperforming the province (by 15 points) while obscuring that disabled students trail all Delta students by approximately 6 points (81.4% for all students vs 75.6%). The gap is narrower here, but the rhetorical strategy remains—compare to worse outcomes elsewhere rather than to the outcomes Delta produces for non-disabled students. |

| Grade 4 FSA Numeracy | “Perhaps most striking was the performance of students with diverse abilities, who made substantial gains from 32.7% to 51.8%, nearly aligning with the provincial average of 52.2%. These improvements suggest that the district’s interventions may be having a meaningful impact, particularly for priority learner sub-populations.” | Disabled students improved 19 percentage points year-over-year, which is substantial. But “nearly aligning with the provincial average” means they’re still below it (51.8% vs 52.2%), and the report doesn’t compare to non-disabled Delta students (likely around 62% based on chart). Delta credits “interventions” without naming them or examining whether the prior 32.7% rate was produced by systemic barriers those same interventions are meant to paper over. |

| Grade 7 FSA Numeracy | “However, students with diverse abilities experienced a decline, dropping from 54.1% to 36.2%, though this remained close to the provincial average of 38.9%. This decline will require further investigation.” | Disabled students lost nearly 18 percentage points in a single year (54.1% to 36.2%)—a collapse in performance the report describes as “close to the provincial average” rather than as a crisis. Compare this to Grade 4’s 19-point gain, which was celebrated. The “will require further investigation” is bureaucratic evasion; no hypothesis is offered about whether this cohort experienced exclusion, behavior interventions, attendance barriers, or other systemic harms as they moved through middle school. |

| Grade 10 Numeracy Assessment | “Students with diverse abilities experienced a slight decline from 38.4% to 36.7%, yet remained well above the provincial average of 29.5%.” | Disabled students are 3.1 percentage points below where they were the year before, continuing a downward trend from Grade 7. Delta frames being 7 points above the provincial average as success, but doesn’t compare to the all-student Delta rate of 39.8%—meaning disabled students are still roughly 3 points behind their peers. The report never asks why numeracy performance for disabled students consistently declines as they progress through secondary school. |

| Grade 7 transition & middle school drop | “As a school district, we are working to better understand and improve math learning for all students, especially those who face learning challenges. One area of concern is the sharp drop in math performance among students with diverse learning needs around Grade 7.” | This is the closest the report comes to naming a pattern: disabled students experience a “sharp drop” in Grade 7. But the framing—”face learning challenges”—locates the problem in students rather than in what the system does to students around Grade 7 (increased behaviour management, transition to secondary structures, withdrawal of support, etc.). The report offers no analysis of exclusionary discipline data, attendance barriers, or IEP quality during this critical transition period. |

| 5-year graduation rates | “Similarly, for students with diverse abilities, Delta students achieved an 85% graduation rate compared to the provincial rate of just over 70%.” | Disabled students are 9 percentage points behind their non-disabled peers (85% vs 94%). Delta celebrates outperforming the province while obscuring that within Delta, disabled students are still 1.7x more likely not to graduate. The report does not examine how many of these students experienced exclusionary practices (room clears, part-time attendance, “safety plans”) that delayed or derailed graduation. |

| Evergreen certificates (non-graduation pathway) | “For a very small number of students in each graduating cohort (<0.01%), the Evergreen pathway provides a tailored educational program directed by each student’s Individual Education Plan. Although the Evergreen is not counted in the Dogwood graduation rates, the Delta School District celebrates the successes of every student and supports each student’s transition to adulthood.” | Delta acknowledges that some disabled students are placed on a non-graduation track (Evergreen certificates) but doesn’t count them in graduation data, then celebrates this exclusion as “supporting transition to adulthood.” The <0.01% figure seems suspiciously low and isn’t contextualised—what percentage of students with intellectual disabilities are encouraged into Evergreen track? The rhetorical move is to make their segregation invisible by excluding them from the denominator. |

| Honours graduation rates (omission) | “When we examine those students who receive an Honours distinction, we see a significant and persistent gap between males and females… For students of Indigenous ancestry, the gap between all resident students expands considerably. The range of honours rates for all resident students between 2020/21 and 2023/24 was 64%-74%. For students of Indigenous ancestry, the range of rates for the same period was 35%-40%.” | The report analyzes honours rates by gender and Indigenous ancestry but completely omits honours rates for disabled students. This is not an accident—it makes the exclusion of disabled students from academic rigor invisible. If 85% of disabled students graduate but their honours rate is not reported, readers cannot see how many are pushed through with minimal standards rather than supported to achieve. |

| Post-secondary transitions | “For resident students with a Ministry designation, we see a significant gap as well, with 35%-45% of students transitioning to a PSI immediately following graduation… when we examine transition data within the first three years of graduation, we see a significant increase in students attending PSI within the three-year window (roughly a 15% increase).” | Disabled students transition to post-secondary at less than half the rate of their non-disabled peers (35-45% vs 60-64%). Delta reports this gap but offers no analysis of why—were students tracked into non-academic courses? Did behavior interventions result in records that affect admissions? Were students told post-secondary “isn’t for them”? The 15% increase over three years is framed as positive but actually suggests delayed entry (working to save money, attending upgrading programs, recovering from school-based trauma). |

| Assessment participation rates | “Furthermore, 84% of Delta students with diverse abilities completed the assessment in Grade 10, compared to the provincial rate of 73.2%.” | While Delta’s 84% participation rate exceeds the provincial rate, this means 16% of disabled students did not participate in the Grade 10 Literacy Assessment—a graduation requirement. The report does not examine why: Were they exempted due to “accommodations”? Were they in Evergreen programs? Had they already left school? The celebration of high participation obscures the 1-in-6 students who are missing from the count. |

| “Priority populations” framing | “Priority populations include approximately 600 students (4%) identifying as having Indigenous ancestry and more than 2,000 students (~12%) with Ministry-identified disabilities or diverse abilities that require varying levels of support.” | Delta uses “diverse abilities” as euphemism and “priority populations” to frame disabled students as a special category requiring more rather than as students experiencing systemic barriers. The “varying levels of support” language implies the problem is individual student need rather than systemic failure. Nowhere does the report name that 12% of students experiencing lower achievement, lower graduation rates, and lower post-secondary transitions suggests widespread institutional harm—not individual deficit. |

| Readtopia pilot for students with intellectual disabilities | “Readtopia Pilot: The goal of this pilot is to examine and implement promising, evidence-based instructional practices to increase literacy for students with intellectual disabilities.” | The report describes a specialised literacy program pilot for intellectually disabled students without examining why these students need a separate program at all. There is no discussion of whether general education literacy instruction is inaccessible, whether these students have been segregated from peers, or whether the “evidence-based” program is actually structured literacy that all students would benefit from. The pilot frame suggests experimentation on the most marginalised students rather than universal design. |

| MathMinds program (no disaggregation) | “Looking more closely at our FSA data, we have compared MathMinds schools to non-MathMinds schools. What we see in both Grade 4 and 7 FSA results is that non-MathMinds schools have generally declined over the past 5 years, while MathMinds schools mostly show growth after they start the program.” | The report analyzes MathMinds impact by school but does not disaggregate by disabled vs non-disabled students within those schools. This makes it impossible to know whether the program reduces gaps or whether disabled students are excluded from the program, tracked into alternative instruction, or simply don’t benefit at the same rates. The absence of this analysis is conspicuous given disabled students’ numeracy struggles are repeatedly flagged. |

| Local literacy data: catastrophic early failure | “Percentage of Learners with Diverse Abilities who are proficient or extending on foundational reading skills (term 3): Grade 1: Oral Reading Fluency 28%, Phonics 23%, Phonemic Awareness 34%, Report Card Score 23%; Grade 2: Oral Reading Fluency 40%, Phonics 30%, Phonemic Awareness 32%, Report Card Score 31%” | The local data reveals that 70-77% of disabled Grade 1 students are not proficient in foundational literacy skills, and 60-70% of disabled Grade 2 students are not proficient. These are catastrophic rates of reading failure in the earliest grades—yet the report presents them in a table without interpretive comment. No discussion of whether these students are receiving evidence-based reading instruction, whether behavior management is interrupting instruction, whether they’re being excluded from class, or whether teachers have the training to teach disabled students to read. The data is disclosed but its meaning is buried. |

| Summary: “closing achievement gaps” | “For those students who are in priority learner sub-populations, we have observed similar upward trends that are beginning to close the observed systemic achievement gaps. Despite this positive trend, we will continue our focus on closing these achievement gaps altogether.” | The report frames persistent, measurable gaps in achievement, graduation, and post-secondary transition as “beginning to close” rather than as ongoing institutional failure. The phrase “systemic achievement gaps” treats the gap as the problem rather than the system that produces it. “Closing gaps” becomes the goal rather than eliminating the exclusionary practices that create them. This is the fundamental rhetorical move of the FESL framework—measure disparities, celebrate modest improvements, never name the violence. |

What this reveals about the Framework’s design

Delta’s report is not evidence of Delta’s failure. It’s evidence that the Framework’s design produces exactly this kind of report when districts follow its requirements:

- Self-assessment without verification means districts determine their own effectiveness with no external accountability

- No minimum standards for “effective” means marginal improvements can be reported as success even when gaps persist or widen

- Vague strategy descriptions mean it’s impossible to assess implementation fidelity or replicate successes

- Data requirements that exclude exclusion mean the mechanisms producing poor outcomes remain invisible

- “Continuous improvement” framing means there’s never urgency—every failure becomes an opportunity for more investigation, more adjustment, more planning, stretching across years while children experience harm now

- No resource adequacy assessment means districts can identify effective strategies but lack capacity to implement them, yet this resource gap never becomes the ministry’s problem to solve

Delta is trapped in an impossible situation: underfunded yet expected to serve all students, over-reported yet given no additional resources for reporting work, under-supported yet held responsible for outcomes, and unaccountably accountable—given no enforceable standards, adequate resources, or consequences for persistent failure. Delta did what the Framework asked. They produced a compliant report. The problem is that compliant reports under this Framework can coexist with ongoing harm to disabled children, because the Framework measures outcomes while hiding the exclusion that produces those outcomes.

The transparency problem: public reporting that obscures rather than reveals

The Framework presents itself as a transparency and accountability mechanism, requiring districts to publish annual reports that include visualisations of provincial data and descriptions of strategic priorities and progress. But transparency is not simply the publication of information—transparency requires that the published information actually reveals what communities need to know to hold systems accountable, that data is presented in ways that allow meaningful public understanding, and that reporting timelines enable action in response to what reports reveal.

The Framework fails on all three counts.

Reports designed for compliance, not comprehension

Districts must submit annual Enhancing Student Learning reports between June 30 and September 30, with a suggested maximum length of 10 pages (excluding data visualisations). The reports must include visualisations of all required provincial measures, disaggregated by priority populations, alongside brief interpretations and analyses. Districts must describe their strategic priorities, community engagement processes, and adjustments made based on data review.

This structure produces documents that feel comprehensive while revealing little. The 10-page limit ensures reports remain at a high level of generality, providing summary statements about priorities and progress without detailed analysis of what strategies were actually implemented, how resources were allocated, which students were served and how, what barriers were encountered, or why gaps persist despite stated commitment to continuous improvement. The requirement to include all mandated data visualisations means the reports are heavy on charts and light on substantive explanation of what those charts mean or what the district is doing in response to concerning trends.

More critically, the Framework provides no guidance on how districts should report on areas where data is masked due to small population sizes. The Q&A document acknowledges this tension (Q10), noting that data sets of fewer than 10 students must be masked according to privacy policy, but that districts “should use unmasked data to have required discussions internally.” What this means in practice: districts can have conversations about subpopulations that are invisible in public reporting, make decisions based on data the public cannot see, and then publish reports that appear comprehensive while obscuring precisely the populations most likely to be experiencing harm—disabled students in small categories, Indigenous students in districts with small Indigenous populations, and children in care in every district.

The Framework describes this as a privacy protection, which it is, but it is also a transparency evasion. Small numbers become invisible numbers become unaccountable practice.

Reporting timelines that delay accountability

Districts submit annual reports to the ministry between June and September. The ministry’s review team then examines each report “within one month of submission.” This means a report submitted in late September might not be reviewed until late October. The review process includes “discussion with the district,” and based on review outcomes, “targeted supports will be determined for continued capacity building.”

This timeline structure ensures that by the time concerning patterns are identified, reviewed, discussed, and translated into capacity-building supports, the school year during which the concerning outcomes occurred is already over. The children who experienced those outcomes have moved on—graduated, transitioned, or in some cases stopped attending because the system failed them. The supports that might eventually reach the district will benefit future cohorts, assuming those supports materialise and prove effective, but they will not remedy the harm already done.

This is accountability as temporal deferral. The Framework treats continuous improvement as a patient, iterative process unfolding across years, even as actual children experience urgent harm in the present. The review cycle is mismatched to the pace of childhood—by the time a district’s persistent exclusion of autistic students is identified, reviewed, discussed, and potentially addressed through capacity building, the specific autistic children whose data revealed the pattern are no longer in the system.

The temporal problem: delay as governance strategy

The Framework’s operational architecture relies on delay mechanisms that convert urgent student harm into patient bureaucratic process. This temporal structure is not incidental—it is how the Framework manages to appear responsive while systematically deferring intervention.

Enforcement delay

The support continuum (communicate → facilitate → cooperate → direct) positions ministerial intervention as the final escalation requiring repeated district failure before consequences materialize. Districts can exclude disabled children for years, report poor outcomes annually, and receive “capacity building” rather than investigation or remedy. Only after exhausting patient support does the ministry consider directive action—and even then, such action remains discretionary, triggered by procedural failures rather than student harm.

Reporting delay

The reporting timeline detailed in the transparency section ensures that concerning patterns are identified months after the school year when harm occurred has ended. Districts submit reports June through September, ministry review occurs within one month, discussions follow, supports are determined – meaning children who experienced harm have moved on before interventions reach their district.

What the Framework means for families right now

The Framework’s abstract procedural architecture produces concrete consequences for families advocating for their disabled children’s educational rights. Here is what the Framework’s evasion mechanisms look like when you are living them:

- Your autistic child is on a partial schedule. They attend three hours daily instead of full-time. The district frames this as “building capacity” for full attendance. The partial schedule does not appear in any Framework reporting. The district receives full per-student funding. Your child’s chronic absence becomes statistically invisible. Their academic gaps will be attributed to disability rather than to access deprivation. The Framework will eventually measure whether they graduate, but never measure the year of education the district denied them.

- You request accommodations in your child’s IEP. The district delays, deflects, cites budget constraints. You file an internal complaint—months pass. You escalate to the Ombudsperson—more months. You eventually reach Human Rights Tribunal if you can afford representation. None of this appears in Framework reporting: not the accommodations you requested, not the refusals you received, not the advocacy labour you performed, not the timeline of delay. The district will report your child graduated, treating this as success rather than achievement despite systemic barriers.

- Your Indigenous child reports declining sense of belonging on the Student Learning Survey. The district’s Framework report acknowledges this is “troubling” and describes being “committed to understanding root causes.” But the Framework establishes no timeline for response, no concrete action plan, no accountability mechanism ensuring the district does more than investigate. Your child’s distress becomes a data point for reflection, not urgent harm requiring immediate intervention.

- Your PDA-profile child experiences repeated room clears. They are removed from the classroom multiple times weekly. These removals are not counted, tracked, reported, or subject to disproportionality analysis. You request the district reduce room clears and implement collaborative problem-solving approaches. This request is framed as parental preference, not disability accommodation. Your child eventually stops attending because repeated removal has made school unbearable. Their chronic absence might be noted internally but never appears in Framework reporting disaggregated by designation. The Framework will measure whether they graduate, but never measure whether the district’s exclusionary practices made graduation impossible.

- You are forced to keep your child home because school “doesn’t feel safe.” You perform unofficial partial schedules the district frames as “parent choice.” The district does not report this as exclusion—your child is “voluntarily” absent. Their academic outcomes suffer. The Framework captures the outcome gap but never the district practices that produced it. You hire an advocate, spend thousands of dollars, escalate through every available process, eventually secure some accommodations. None of this labour, cost, or timeline appears in district reporting. The Framework measures your child’s eventual achievement as if it were the natural result of their disability, not the predictable consequence of denied access.

The Framework promises continuous improvement while enabling ongoing harm. It produces reports that allow districts to narrate their equity commitment while disabled children experience exclusion the reports never name. It asks families to trust iterative planning processes unfolding across years while children’s school careers unfold across finite childhoods that cannot wait.

The familiar architecture of narcissistic deflection, scaled to governance

Parents who have survived years of advocacy battles recognise instantly the conversational architecture of narcissistic deflection: the centring of the harm-doer’s good intentions over the harmed person’s material reality, the demand for recognition of effort expended rather than accountability for outcomes produced, the reframing of your child’s exclusion as evidence of the system’s care, the insistence that you acknowledge how hard everyone is trying while your daughter loses instructional time and your son gets cleared from rooms. You learn to identify the moment in every IEP meeting, every principal conversation, every district response when the focus shifts subtly from your child’s experience to the emotional labor of the adults managing your child, when “we care so much about him” becomes the answer to “why is he on a partial schedule,” when your documentation of harm gets met with wounded defensiveness about how dedicated the staff are, how constrained the resources, how complex the situation.

This is not merely frustrating communication—it is the operational logic of systems that cause harm while requiring recognition for their good intentions, systems that transform accountability conversations into opportunities for the institution to center its own subjective experience of trying hard under difficult conditions rather than confronting the material consequences of its choices on the bodies and futures of actual children.

To recognise this same narcissistic architecture operating at the provincial policy level—in a Framework that demands recognition for its elaborate planning processes, its sophisticated measurement systems, its commitment to equity and continuous improvement, while refusing to prohibit the exclusionary practices causing the outcomes it claims to want to change—is not merely disappointing; it is a particular kind of violation, because it reveals that the pattern you thought might be individual failures of particular educators or administrators is actually embedded in the ideological machinery of governance itself, that the same refusal to center impact over intention operates at every scale simultaneously, from the teacher who needs you to understand how distressed she feels about your son’s behaviour through to the Ministry that needs you to appreciate the comprehensiveness of its accountability framework while that framework systematically protects the conditions producing your family’s suffering.

The Framework performs exactly the conversational moves you have learned to recognise as narcissistic deflection: it centres its own sophistication and rigour, demands recognition for the complexity of its design and the sincerity of its equity commitments, becomes defensive when you point out that disabled children remain excluded under its oversight, redirects focus from substantive harm to process compliance, treats your insistence on material change as failure to appreciate how hard the system is working within its constraints. It measures everything except what matters, reports on harm without stopping it, escalates consequences for administrative failures while protecting substantive violence, then positions this architecture as evidence of its deep commitment to the very children it continues to exclude—requiring you to acknowledge the Ministry’s good intentions while your children experience the impact of its refusal to commit resources, prohibit coercion, or establish concrete targets for change.

This is intention as shield against accountability for impact, elevated to the level of provincial policy: a system that can feel good about itself, that can point to its elaborate equity infrastructure and continuous improvement cycles as proof of its values, while disabled children remain systematically excluded because the system refuses to define exclusion as the accountability failure requiring intervention, because intention—evidenced through planning, measurement, and process—becomes the metric of success rather than the lived reality of children who survive or do not survive its operations.

When you have spent years learning to identify and resist narcissistic conversational patterns in interpersonal advocacy contexts, when you have developed the skills to refuse deflection and insist on centring your child’s material experience over adult feelings and institutional constraints, to encounter that same pattern embedded in the structure of governance itself—not as individual failure but as systemic design—is to understand that you are not fighting scattered problems requiring scattered solutions, but rather a coherent ideological apparatus that operates consistently across every level of the system to protect itself from accountability for the violence it enacts, that the narcissism is not incidental but foundational, that the refusal to center impact over intention is not a communication problem but the organising principle of the machinery itself.

-

Epistemic silencing of disabled children’s primary caregivers

Epistemic silencing in BC schools discredits mothers’ knowledge, reframes advocacy as aggression, and erases disabled children’s pain, leaving families punished for truth.

What genuine commitment would look like

If the Framework were designed to actually improve outcomes rather than manage the appearance of oversight, its architecture would require five foundational elements the current Framework systematically avoids: ambitious measurable targets with timelines (not endless “continuous improvement”), comprehensive data transparency including exclusion and access measures (not just academic outcomes), adequate dedicated funding for inclusion infrastructure (not budget ventriloquism forcing districts to reallocate existing inadequate resources), timely enforceable consequences triggered automatically when districts fail to meet standards (not patient capacity-building that defers intervention indefinitely), and explicit rights-based language establishing what disabled students are entitled to receive and what districts are obligated to provide (not procedural compliance language treating inclusion as aspiration rather than entitlement). These elements would transform the Framework from performance management theatre into an accountability mechanism capable of actually protecting disabled children from the exclusionary practices BC districts currently deploy with impunity.

Accountability theatre in an age of manufactured scarcity

The Framework for Enhancing Student Learning is a masterwork of institutional evasion—a policy architecture that appears rigorous, equity-focused, and evidence-driven while systematically avoiding every mechanism through which it could actually hold districts accountable for serving disabled students or compel meaningful change in exclusionary practices. It establishes an elaborate apparatus for planning, reporting, reviewing, and capacity building that produces the aesthetic of continuous improvement while preserving district autonomy where it matters most: in the capacity to continue excluding disabled children without consequence, remediation, or enforceable timeline for change.

This is governance designed to withstand critique rather than respond to it. When advocates point to persistent outcome gaps, the ministry points to the Framework’s reporting requirements. When families describe exclusionary practices, the ministry points to capacity-building supports. When tribunal decisions identify systemic discrimination, the ministry points to strategic planning cycles and iterative review processes. The Framework becomes an institutional shield, deflecting demands for urgent intervention by producing the appearance of institutional attentiveness while deferring actual change indefinitely into a future that never quite arrives for the children experiencing harm in the present.

The Framework’s design reveals the values that actually animate BC’s approach to disabled students: procedural compliance over substantive protection, district autonomy over student rights, gradual improvement rhetoric over urgent intervention, and scarcity management over adequate resourcing. It treats the persistent exclusion of disabled children from public education as a data interpretation problem rather than a rights violation, a capacity gap rather than a policy choice, and a planning challenge rather than an ongoing crisis demanding immediate remedy.

What disabled children in BC need is not another iteration of continuous improvement planning—it is a provincial government willing to establish ambitious targets, fund adequate support, measure exclusion alongside outcomes, and enforce consequences when districts fail. What we have instead is a Framework that asks districts to improve without defining what improvement looks like, demands equity without funding inclusion, and promises accountability while systematically evading the transparency, enforcement, and urgency that accountability requires.

Children excluded today—sent home early, kept home by “parent request,” placed on partial schedules, room cleared until they learn not to come to school at all—cannot wait for continuous improvement cycles to eventually reach them. They are entitled to protection now, accommodation now, inclusion now, and enforcement now. They do not need another strategic plan investigating concerning data patterns. They do not need capacity-building webinars that might change practice in future years. They do not need patient, iterative processes respecting district autonomy while districts deploy exclusionary practices with impunity. They need a provincial government willing to name exclusion as a rights violation, measure it as rigorously as academic outcomes, fund inclusion adequately rather than perform budget ventriloquism, establish ambitious targets with enforceable timelines, and intervene immediately when districts fail. Until the Framework centres disabled children’s rights with the same rigour currently devoted to procedural compliance, it remains accountability theatre performed for an audience who deserve better than performance—they deserve protection, and they deserve someone willing to trust the truth of what they already know better than to trust the performance.

-

Government funding for education fails to keep pace with known needs

The Education and Childcare Estimate Notes 2025 reveal a province experiencing an enormous rise in disability designations while preparing the minister with polished assurances that gesture toward progress, equity, and commitment, and this dual presentation of crisis beneath a veneer of stability creates…