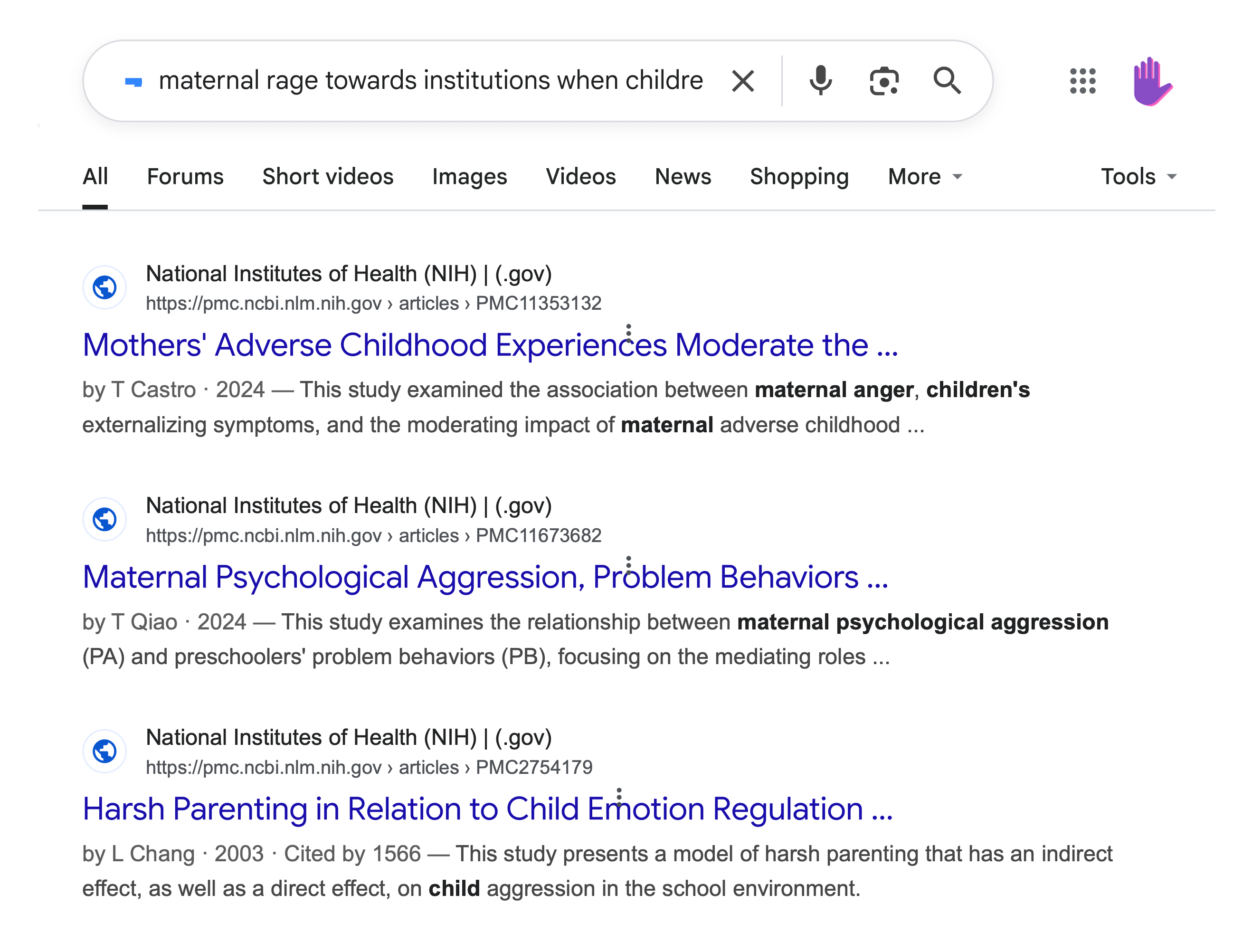

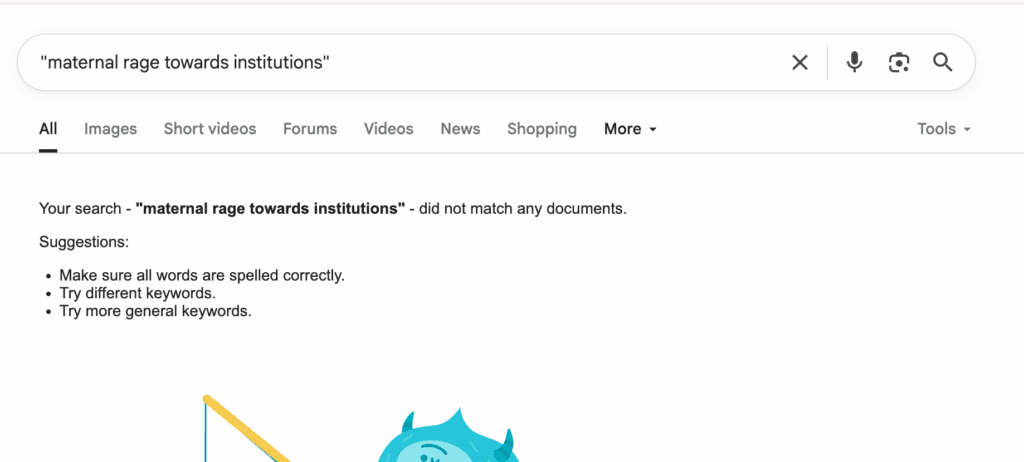

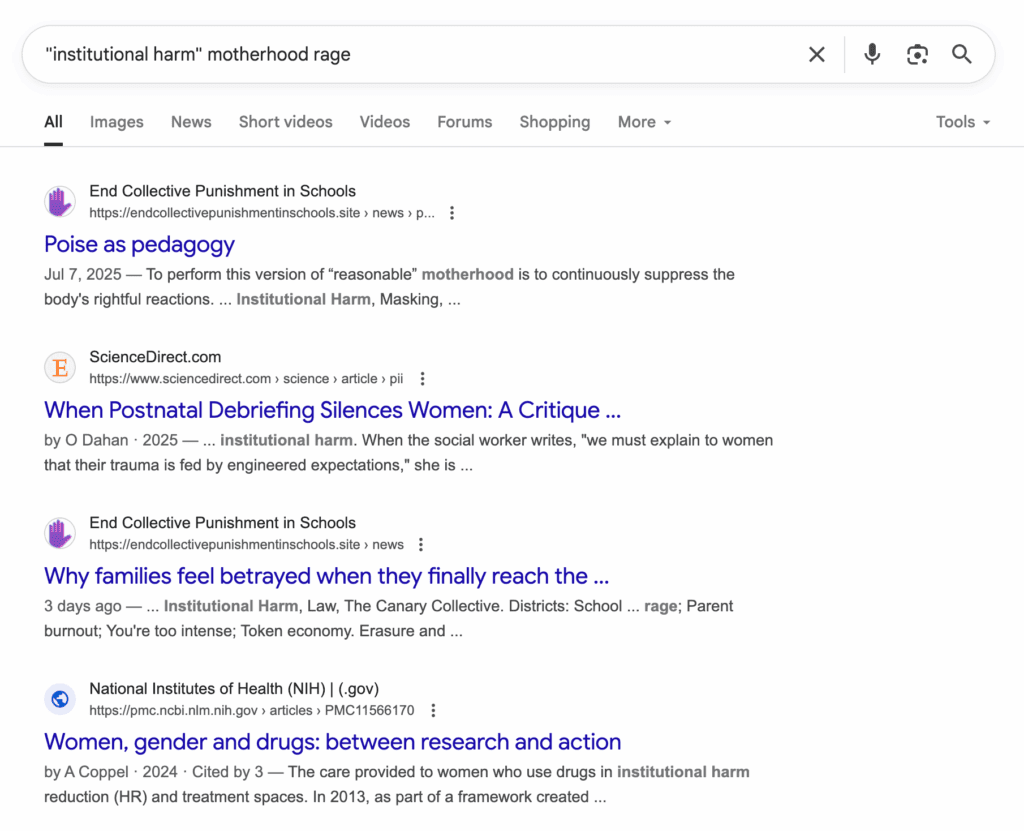

I searched for literature that affirms what I know in my body—that maternal rage can be righteous, grounded, and deeply linked to the betrayal of public institutions. But what I found instead was an avalanche of studies examining how maternal anger harms children. The field catalogues the psychological effects of maternal yelling, tracks the correlations with aggression, and medicalises the mother’s emotion as pathology. Almost nothing addresses the structural conditions that provoke the rage. The rage is extracted from context. The wound is measured only in the child, never in the mother.

This is a diagnostic erasure. It treats the mother’s body as the problem rather than the institution that failed her child. It speaks in terms of risk and regulation, not betrayal and justice. The result is a research landscape where harm is always traced back to the mother’s nervous system, never to the system that pushed her beyond capacity, ignored her pleas, and called her combative when she refused to disappear.

The silence is its own form of harm. It likely leads many women to personalise systemic injury. But this absence is not incidental. It is a structurally produced gap. The silence emerges from conditions that make speech nearly impossible: burnout, legal entanglement, NDAs, family court coercion, reputational risk, and the pathologisation of maternal emotion. These constraints do not merely limit expression; they foreclose the possibility of research.

The institutions that provoke this rage are the same ones that control the frameworks of legitimacy. By naming these barriers, this essay challenges the presumption of neutrality in academic inquiry and positions lived experience as a source of counter-knowledge. If maternal rage is the body’s protest, and epistemic silencing is the intellectual containment, then designed for despair is the affective strategy that binds them.

Toward an archive of epistemic survival

There is a name for what I am experiencing: the epistemic silencing of disabled children’s primary caregivers. This is not an incidental consequence. It is a targeted outcome. Because the knowledge we carry threatens the systems that depend on their own self-concealment. This historiological war results in a kind of brutal censorship, mangling our words before the scream can leave our throat, through chronic dismissal, bureaucratic delay, diagnostic suspicion, and the strategic withdrawal of access.

They record the rage but discard the record—the files, the timelines, the documentation that might have grounded it. They provoke the scream, then cite it as evidence. It is a strategy designed to inflame and discredit, to draw the mother into a performance of desperation so they may withhold access until she simpers, apologises, and begs for scraps.

I now understand that what I am writing is not merely testimony. It is scholarship forged under duress, a dissertation on muffled screams and procedural forgetting, authored without institutional permission. It is the record they said could not exist.

I am documenting what happened to my children and to me, because I don’t think it’s an isolated mistake. I would rather tell a thousand strangers the most intimate parts of my pain than return to another institution and beg it to believe what I already know.

-

Epistemic silencing of disabled children’s primary caregivers

Epistemic silencing in BC schools discredits mothers’ knowledge, reframes advocacy as aggression, and erases disabled children’s pain, leaving families punished for truth.

Testimonial injustice and epistemic violence

Miranda Fricker’s theory of testimonial injustice offers a sharp framework for understanding how institutions discredit maternal knowledge. When mothers speak from lived experience—especially about harm to their disabled children—they are often granted a credibility deficit rooted in identity-based stereotypes. The injustice here is twofold: it is ethically wrong to dismiss truth based on the speaker’s social identity, and it is epistemically dangerous, because it suppresses essential knowledge about institutional harm.

As Emily McWilliams explains, such injustice becomes culpable when it persists in the face of clear evidence. In my experience, this is not theoretical—it is the rule.

“Testimonial injustice (TI) is the name given by Miranda Fricker (2007) to a phenomenon that she identifies as the primary form of epistemic injustice – injustice done to one in their capacity as a knower. TI happens when, in attempting to convey knowledge through testimony, a person is subject to an identity-prejudicial credibility deficit. For Fricker, instances of TI are both epistemically and ethically culpable….

Epistemic culpability comes in with stereotypes that are prejudicial in the sense that they involve a prejudgment that is “made or maintained without proper regard to the evidence (2007, p.33).” Prejudices, for Fricker, are judgments that display resistance to counter-evidence. Absent mitigating circumstances, she says, resistance to counterevidence makes such judgments epistemically culpable.”

Testimonial Injustice and the Nature of Epistemic Injustice by Emily Colleen McWilliams

Kristie Dotson sharpens this terrain by introducing the concept of epistemic violence, a form of epistemic oppression that does not merely reduce credibility—it extinguishes the very possibility of recognition. Epistemic violence unfolds when marginalised speakers attempt to contribute knowledge and are met with structural or relational refusal. It is not disbelief. It is preclusion. It is the decision—whether tacit or procedural—that what this person says is unhearable, that what she knows is untranslatable within the institution’s epistemic frame.

The mother speaks, slowly and precisely, carrying years of documentation, layers of grief, and a voice tempered by exhaustion; the institution responds with silence, or with delay, or with a procedural nod so vague it feels like vanishing. There is no misunderstanding here, only an orchestrated refusal to create the conditions for understanding. For mothers who are neurodivergent, trauma-informed, or politically unwilling to perform compliance, the clarity of their words is not debated—it is deflected. The school offers no rebuttal, only euphemism. It channels pain into paperwork, translates harm into tone, reroutes grief through protocol until it no longer appears on record. The mother remains vivid and present, but her truth becomes weightless in the institutional ledger—a ghost rendered illegible by design.

This is institutional violence disguised as indifference—a calibrated refusal to hear the truth, orchestrated through performance and protocol, as if the act of ignoring grief were a form of policy. The very utterance is framed as betrayal. The mother becomes dangerous for daring to speak. And in that framing, the institution protects its coherence by silencing the one who might rupture it.

This is how the harm repeats. This is how systems remain intact. They deny the conditions under which repair could occur. They extinguish the very possibility of institutional learning.

Institutional betrayal and the mother as threat

Jennifer Freyd names this dynamic institutional betrayal: the psychic rupture that occurs when a system tasked with care instead inflicts harm. The betrayal pierces deeper than neglect because it violates a sacred expectation. It manipulates trust to facilitate harm. Feminist readings of moral injury, such as those emerging from the work of Susan Brison, Laura Brown, and extend this idea: when institutions suppress harm to preserve their moral image, they transfer the injury to those who remain awake. Those who speak are cast as disloyal. Those who refuse to soften are treated as hostile. The injury accumulates in the one who sees.

Sara Ahmed’s work on complaint, institutional will, and the feminist killjoy offers a map for this terrain. She shows how institutions reflexively fail to hear truths that endanger their coherence. “Threatening the face” of the institution means that no idea—however thoughtful or carefully researched—can be accepted if it comes from the mother who has seen too much.

Professionals recoil from her clarity. Administrators retreat into process. Advocates lower their eyes. In the presence of unflinching maternal truth, even allies vanish. She will always be treated as inappropriate—too emotional, too precise, too unwilling to forget. No idea can be adopted if it originates from the mother who knows more than the institution.

Psychoanalytic framings of narcissistic injury deepen this understanding. Institutions, like brittle egos, lash out at truth-tellers not because their words are false, but because they pierce the fantasy of goodness. The rage is against recognition. The silencing is an act of self-defence.

When a mother names the harm precisely and refuses to simper, the system renders her voice illegible and dangerous. She ruptures the institutional ego. She exposes the performance of care as theatre, not remedy. Worse, she makes the harm real.

The mother as threat

I’ve written before that this system is designed to exhaust. But exhaustion is only the surface tactic. The deeper strategy is erasure—of knowledge, of grief, of clarity, of the mother herself. When a mother names the harm precisely and refuses to simper, the system renders her voice illegible and dangerous. She ruptures the institutional ego. She exposes the performance of care as theatre, not remedy. Worse, she makes the harm real.

Feminist thinkers like Adrienne Rich, Patricia Hill Collins, and Lisa Baraitser have explored how maternal knowledge unsettles institutional comfort. When a mother stops performing composure and begins to speak with moral authority—when her rage arrives not as dysfunction but as diagnosis of institutional harm—she becomes politically unmanageable. Her clarity requires response. Her refusal to forget demands reckoning. Her words carry weight that cannot be absorbed without consequence.

And so I ask myself—what if I did something else entirely? What if I built something different—not based on extraction, but on collective presence?

Truth without permission

I have heard it again and again in the whispered testimonies of parents—some bound by nondisclosure agreements, some speaking through tears, some pacing through parking lots with earbuds and strollers and trembling hands—all arriving at the same brutal conclusion: You need a lawyer. Then everything will start working. If you have money, please get one immediately.

What haunts me is not just the cruelty of that sentence, but the clarity it reveals—that this so-called remedy, this brittle, contingent access to justice through legal threat, is only available to those who can afford its toll. I could liquidate what remains. I could sell my safety, mortgage my future, drain my account and my nervous system alike, just to hire the only kind of voice the institution respects. And maybe then the school would listen?

And even if the system arrived now with apologies and gold-plated promises, it would still arrive carrying the stench of broken promises. My child has already been broken in full view, and the institution turned away. My son has been in bed since March. My daughter carries trauma no child should be asked to handle. Their joy, their trust, their felt sense of safety has been reshaped by institutional betrayal. There is no policy that can reverse that.

So I ask myself: what if I refused to pay for credibility with the last fragments of my stability? What if I built something different? What if we made truth matter without requiring litigation? What would it mean to centre the children whose caregivers carry clarity but no capital, whose families are watching this system collapse in slow motion with no leverage to intervene?

What would it take to build a remedy that does not depend on sacrifice, but on recognition? One that treats a mother’s voice as testimony.

-

The poison of silence: on complicity, healing, and speaking the truth

I had so much pain stuck in my chest and throat. Cancelled screams. Unsaid truths. Every meeting where I stayed quiet, every time I swallowed my words to seem reasonable, every time I hoped that portraying myself a certain way might stop my…