When schools perform inclusion while enacting exclusion, the evidence accumulates in objects and spaces, in the material culture of neurodivergent childhood, in the things that were meant to help but became instruments of control, in the architecture that promised safety but delivered abandonment. These are the objects that witnessed what happened to my children in BC public schools, each one a testament to accommodations refused, regulation prevented, participation made impossible, and blame redirected onto the bodies of disabled children and their failing mothers.

The box

The box was meant to hold regulation tools, fidgets my son needed to stay present in his body, to manage the sensory assault of the classroom, to remain anchored when everything around him pulled him toward dysregulation. They decided to make having fidgets a universal accommodation. His education assistant made the box as part of a class activity, and the fidgets I sent to school were supposed to go inside. When students kept reaching for their boxes without asking permission, the boxes were moved to the resource room and locked away, transformed from support into contraband, from accommodation into something that required supervision and control.

I sent more fidgets to school. They were removed from his desk, placed in the box, locked in the resource room. I sent more. They were removed again. By the end of the year I had ordered three hundred dollars worth of fidgets, a mother’s frantic attempt to outnumber the system’s refusal, to flood the classroom with enough tools that surely some would remain within his reach. At year-end pickup they handed me a huge box heavy with fidgets, enough for five classrooms, a year’s worth of accommodation transformed into evidence of excess, of a mother who kept trying to solve a problem the school refused to acknowledge.

The bathroom stall

The bathroom was supposed to be refuge, the one place my daughter could retreat when the sensory violence of the classroom became unbearable, when she needed to regulate her nervous system away from the fluorescent lights and the social performance and the relentless expectation that she remain still and compliant. She would go into the stall to breathe, to reset, to survive the school day.

Boys would gather outside the door and catcall her, shouting crude jokes and taunts through the gap between the door. When she asked the principal for help, for the most basic protection that any child deserves, the principal told her to return to the classroom instead of addressing the boys, instead of making it clear shouting at her through the door was harm that would be stopped. Like daughter as the problem—the one who kept leaving class, the one who needed too much, the one whose body kept requiring accommodation—rather than the boys whose behaviour created the danger.

In high school they closed the bathroom down entirely because girls kept going in there to chat with each other, to escape the intensity of the hallways, to find a few minutes of social connection away from adult surveillance. The school responded by locking the door, removing access rather than addressing why girls needed refuge, why the architecture of the school felt so hostile that the bathroom became the only space that belonged to them.

The lunchroom

Her paediatrician told me her weight had dropped to the first percentile, that her ARFID combined with the sensory hostility of the lunchroom meant she was malnourished, that I should start feeding her a second dinner at night because she could eat at school. I advocated for her and a couple of friends to eat in an alternate space, somewhere quiet where she would be safe from the boys’ cruelty, where she could actually consume food. The school ignored me completely. I advocated for her to keep snacks at her desk so she could eat throughout the day when her body allowed it. The school prevented her from doing so over and over, even after I provided a letter from her paediatrician, even after medical documentation made it clear this was necessary for her survival.

The lunchroom should have been nourishment, a place where my daughter could refuel her body and prepare for the afternoon, but instead it became a daily assault, a space where boys in her class discovered they could weaponise her sensory sensitivities by shouting poop and fart jokes across the table, filling the air with words they knew would make her recoil, make her unable to eat, make her body shut down in disgust and overwhelm. They turned her predictable response into entertainment, her disgust into their game, and she stopped eating at school entirely.

“Each morning I pray she will eat and she comes home in tears, after being teased”

Just a Parent

The tree

The tree stood at the edge of the playground, thirty or forty feet tall, its branches thinning toward the top where they became bendy and weighted down, and when my son became completely dysregulated—when the support that had been holding him steady was withdrawn, when weeks of growing dysregulation culminated in one triggering incident like being pushed on the playground—he would run to that tree and climb to the very top, seeking distance from it all.

Staff and other children would gather at the bottom and yell up at him, some urging him to come down with concern in their voices, others taunting him and making fun of him, turning his distress into spectacle. The pattern repeated over and over: he would receive support during a crisis, seem to stabilise, and then the support would be withdrawn and over weeks he would become more and more dysregulated until something small would tip him over and he would be back in the tree, thirty feet up, while people shouted at him from below.

“Each day I pray he doesn’t fall to his death’

Just a parent

The school called this going from zero to sixty, as if his response came from nowhere, as if the withdrawal of support and the accumulation of stress and the triggering incident were separate from each other rather than part of a single architecture of abandonment, as if climbing the tree was the problem rather than the symptom of everything that had failed him on the ground.

The bag of coats

“Your kids need the proper equipment to be successful at school,”

the teacher said, or something close to that, referring to my son arriving without a jacket that day, framing my parenting as inadequate, as if I had failed to provide the basic necessities required for outdoor play. My children both have ADHD and one with pathological demand avoidance, which means they genuinely do think jackets are unnecessary until they are freezing cold, until their bodies register the temperature in a way that overrides the demand resistance, and by then it is too late.

The school refused the accommodation of helping my children gather their belongings at the end of the day, refused to support the executive function gap that meant jackets stayed in the cloakroom instead of coming home, so I adapted by buying jackets at Value Village every time I saw one, sending jacket after jacket to school knowing I would be judged as a neglectful mother otherwise, knowing that my children’s inability to manage their belongings would be read as my failure to provide.

At the end of the year they handed me a garbage bag filled with every jacket I had sent to school, a collection that felt like both a benediction of my love—proof that I kept trying, kept providing, kept attempting to meet the school’s demands—and an indictment of the institution, evidence that the school had refused the one simple accommodation that would have allowed my children to succeed, that they had chosen to let the jackets accumulate in the cloakroom rather than help my children bring them home.

It shouldn’t be this hard to send your child to public school!

“I hauled the garbage bag to the car, grateful the kids’s Dad had picked them up and immediately burst into ugly loud wails, moral injury and hopelessness making my entire body ache.”

Just a Parent

Pizza day

My son loves pizza, the predictable comfort of cheese and bread and tomato sauce, but neither of my children ever brought home the permission forms, the slips of paper that were supposed to travel from school to home and back again, carrying information about pizza day and hot lunch programs and all the small social rituals that knit children into the fabric of school life. I would search their backpacks and occasionally find something crumpled at the bottom, weeks old, unreadable, and I started to understand that I was being set up to fail, that the school’s communication system required executive function my children did have.

I requested the accommodation of having forms sent home by email, bypassing the paper system entirely, giving me a chance to actually receive the information and respond. Sometimes they complied and sometimes they didn’t, so maybe we missed signing up, and then it would be pizza day—my son’s favourite—and when they started passing out slices to the other children, he would realise he wasn’t getting one.

He would ball his fists and become angry, his body flooding with the injustice of exclusion, with the sensory anticipation of pizza followed by the crushing disappointment of being left out. Staff would feel awkward, aware that his negligent mother had failed to sign him up, and sometimes they would give him a slice out of charity, framing it as generosity rather than acknowledging the system’s failure.

The sticker chart

Schools love sticker charts, the visual performance of compliance and achievement, the public ranking of children’s behaviour translated into stars and smiley faces and team points that accumulate over days and weeks. One time they implemented a chart that relied on teams, where individual children’s compliance or defiance affected the collective score, where my son’s ability to earn rewards depended on the behaviour of children he could not control.

I requested that he be excused from the chart, that he be allowed to opt out of a system designed to intensify social pressure and competition, but the school insisted he was very into it, that he loved the game, that removing him would be a punishment rather than protection. My son started coming home talking negatively about the children on his team, cataloguing their failures, his language growing darker and more vicious, until he was wishing harm on them, wishing they would come to an ill end, his entire internal world colonised by the logic of the chart.

“School isn’t supposed to feel like the Hunger Games.”

Just a Parent

I talked to the school about how the intense competitiveness in my son—the way his brain latches onto systems and rankings and and feeling rules aren’t fair. The school did change the system, but the damage was already done, the lesson already learned: other children were threats to his achievement, their failures were his losses, and he would never want to do a group project again.

-

Why sticker charts fail

Sticker charts and other incentive-based systems promise to motivate children through tangible rewards, yet they too often undermine genuine engagement by teaching students to focus on external validation rather than on the inherent value of learning or participation. When a child’s behaviour is…

The volleyball

When the principal cancelled the volleyball game, she transformed what should have been a moment of joy and collective affirmation into despair and humiliation, converting an opportunity for my daughter to connect and excel with her team into a public lesson where she became marked as the source of everyone’s loss. My daughter and her friends had broken into the gym to play at lunch, cavorting with the boundless energy of children who feel alive together, until they were caught and marched to the principal’s office with the rest of the volleyball team.

The principal told them that because some team members had disobeyed the code of conduct, they might be able to represent the school at the game the next day—maybe, if they wrote apology letters, they could redeem themselves. My daughter refused to apologise to the teacher she had a physical altercation with the week before, and her refusal became the justification for cancelling the game for everyone.

I had asked for the accommodation of avoiding public humiliation multiple times in the past, as my daughter suffers from anxiety tummy and shaming particularly makes her unwell.

Her peers kept asking her why the game was cancelled, their disappointment circling back onto her, their confusion turning into accusation, and she was humiliated. This is the deepest cruelty of collective punishment: it conscripts children into the institution’s logic, making them instruments of discipline, weaponising their disappointment to press guilt into the skin of the child already marked as different. The principal positioned her as the saboteur, the one who had taken something away from everyone else, and once a child is placed in that role, she begins to carry it, to believe that she is the problem, that her place in the group is precarious and dangerous, that her existence is costly to others.

-

The cancellation

When the principal cancelled the volleyball game, she did more than remove an afternoon of play from a group of eager children, she transformed what should have been a moment of joy and collective affirmation into despair and humiliation, converting what should have…

Conclusion

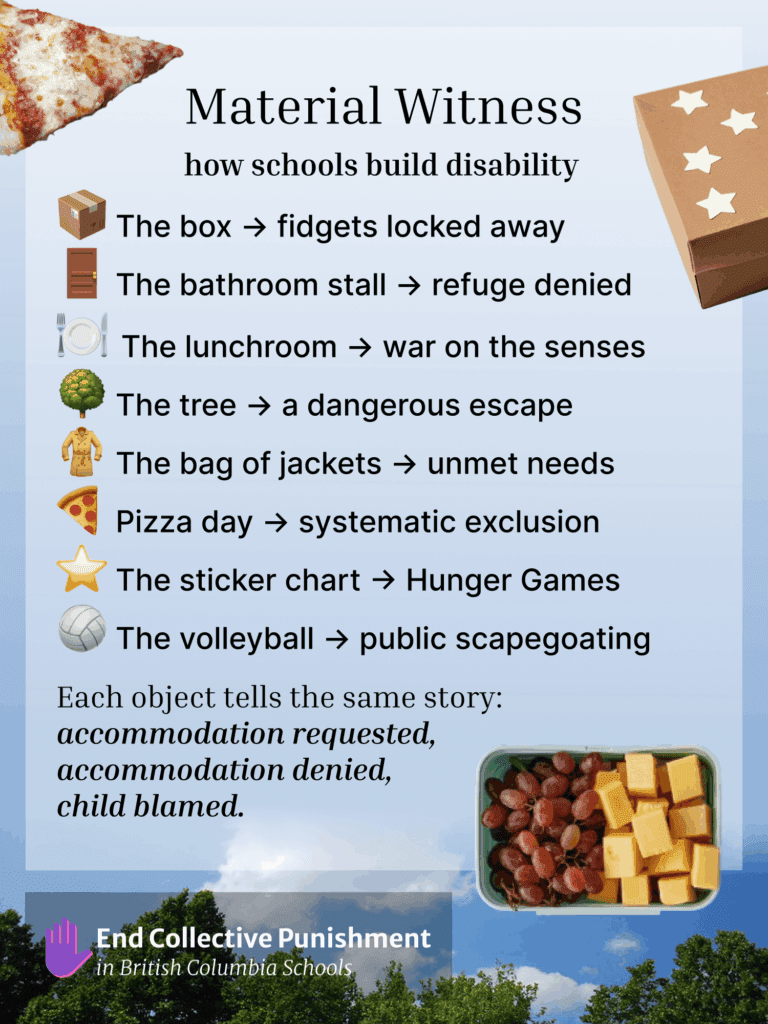

Schools build disability, object by object, space by space, through the accumulation of refusals that pile up like fidgets in a garbage bag, like jackets no one helped gather, like the silence in a locked bathroom, like hunger at a lunch table, like the height of a tree when the ground becomes unbearable. Each object tells the same story: accommodation requested, accommodation denied, child blamed, mother judged, and the institution protected through the performance of inclusion while the practice remains exclusion, abandonment, scapegoating.

These objects are evidence. They witnessed what happened. They hold the weight of what schools refuse to see.

This post was inspired by The Canary Collective’s post Unseen, Unheard, Unprotected: How Accommodations Quietly Disappear. If you’re not following Wren already, you should!