Let’s rip the mask off this polite, professional charade: when schools say a child went from “zero to sixty,” they are lying to protect themselves.

They are covering for the adults who ignored every warning, missed every signal, and left a child to be harassed, baited, and humiliated until their nervous system screamed for survival.

They are turning real human suffering into a mechanical metaphor so they can dodge responsibility for the harm they allowed. And when I heard them use that phrase about my son Robin, I told them straight: he’s not a car. He’s a boy they failed.

Weaponised incompetence is the school’s favourite shield

Every time I see the phrase “unexpected behaviour” in a school safety plan or report, I feel my chest seize with fury. It’s not neutral language—it’s a calculated erasure of everything that came before. This feigned shock is not incompetence; it’s weaponised. It’s the wide-eyed performance of “Who could have known?” when in fact, parents did know, warned them, and laid out the map months or years in advance. Playing dumb is easier than admitting they ignored the truth.

-

There’s no such thing as unexpected behaviour

This piece was hard to write. It holds my grief. It documents not only what happened to my child, but how systems made it worse by pretending to be surprised. I share it because too many families are made to carry this alone. Every time I see the phrase unexpected behaviour in a school document, a safety […]

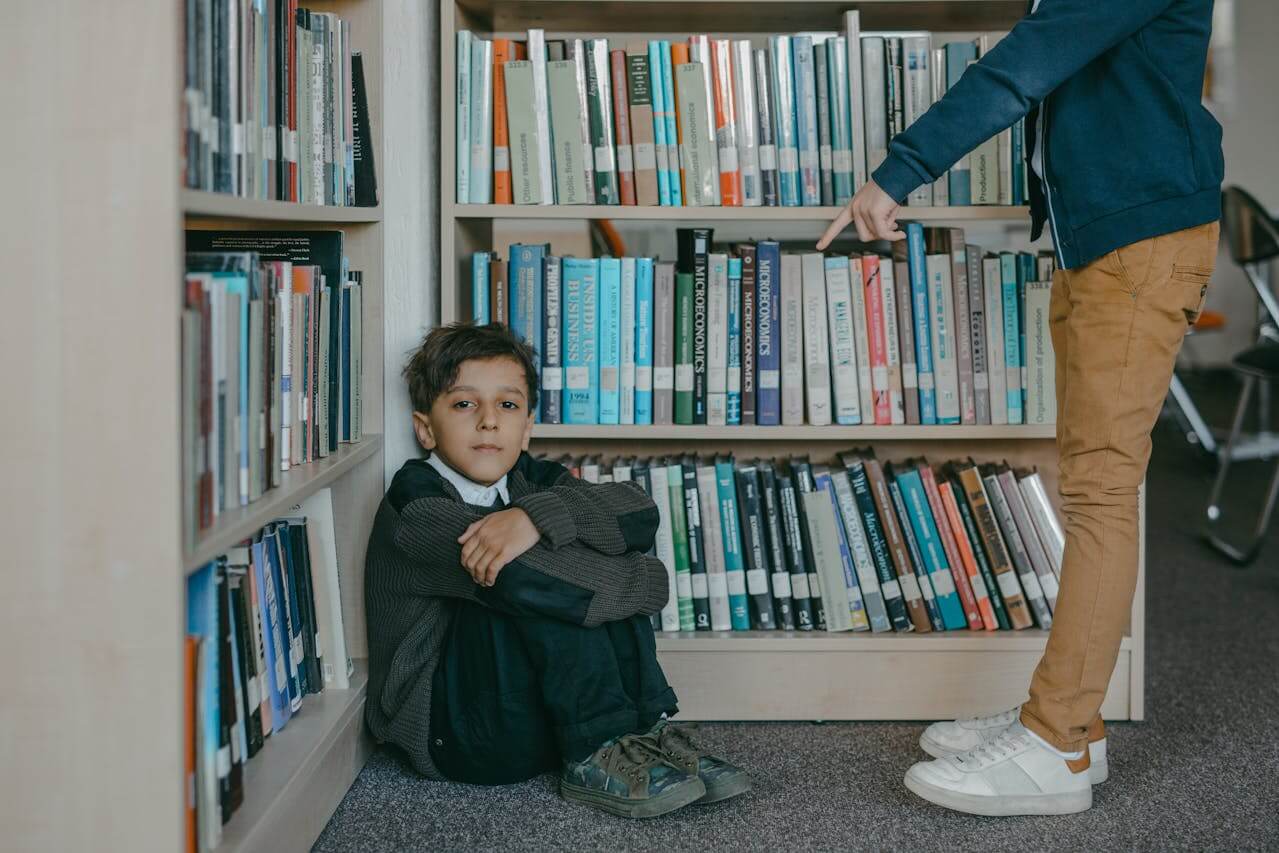

The cruelty starts long before the breaking point

The bite, the shove, the scream—these are never the beginning. They are the end of a long chain of harm the adults refused to name. My son was poked with sticks, called gay as an insult, lied about, taunted, and physically threatened. He scanned the field at recess for danger instead of playing. And still, they kept the focus on his reaction, because acknowledging the harassment would mean admitting they failed to supervise the children, instil a safe culture, or protect him.

When schools refuse to protect, children defend themselves

On the day the biting returned, my son had already tried everything—walking away, saying stop, clearly stating his discomfort. He was ignored. The rope swung too close, the taunts landed again, and his body remembered: this child is a threat, this space is unsafe, and no one will stop it unless I do. He knows biting is wrong. He said so himself. But when a child has been pushed too far, for too long, with no adult willing to step in, survival takes over.

Hiding the real story behind confidentiality and jargon

They hid behind “confidentiality” to avoid talking about the other kids’ behaviour. They refused to say the word bullying. They refused to recognise the calculated cruelty some children aim at those who will react. They refused to connect the dots between repeated provocation and predictable responses. Instead, they made my child’s distress the problem and their inaction invisible.

The truth about “zero to sixty”

This phrase means the school missed every chance to help, ignored the mounting stress, and only reacted when the child finally broke. It means they punished the symptom and erased the cause. It means they arrived too late and then blamed the child for burning when they’d been stoking the fire for months.

You cannot say you care about children and keep doing this

There is no such thing as a child who goes from zero to sixty. There is only a child whose suffering was ignored until their body could not hold it anymore. If you see the bite, the scream, the collapse—you are already too late. The harm has been done, and the blame belongs to the adults who looked away.

-

He doesn’t go from zero to sixty

“He’s not a car,” I said, exasperated, after someone described Robin as going from zero to sixty. The withering look I received in return was pure disgust—as though I had interrupted a sacred adult ritual, as though I may as well have had a huge boil in the middle of my forehead, oozing pus. But […]

FAQ

What does “zero to sixty” mean when schools use it?

It’s a way schools describe a child’s reaction as if it came out of nowhere, erasing the build-up of harm, stress, and provocation that led to it. This framing makes the child the problem instead of the conditions that pushed them to a breaking point.

Why is this language harmful?

It shifts blame from the adults who failed to intervene early to the child who reached their limit. It hides the fact that repeated incidents, ignored warnings, and unsafe dynamics were present long before the visible reaction.

How can I tell if my child’s behaviour is being misrepresented?

Look for patterns in reports that focus only on your child’s final action without describing the lead-up. Watch for phrases like “unexpected behaviour” or “sudden escalation” without details of what happened beforehand.

What should I ask when my child is accused of sudden escalation?

Ask:

- What happened in the hours or days before this incident?

- Who witnessed the interactions leading up to it?

- What steps were taken to protect my child before the reaction occurred?

- Were previous concerns documented and acted upon?

How can I document patterns of harm?

Keep a dated log of incidents, your child’s reports, and any communication with the school. Include details about triggers, witnesses, and the school’s responses. Patterns are powerful evidence. Also see: The paperwork trap: when doing everything right becomes your downfall

What support should I request for my child?

Request proactive measures such as:

- Increased supervision during vulnerable times

- Peer education about bullying and inclusion

- Clear safety plans that address triggers

- 1:1 support if needed for regulation and safety

How can I challenge the “zero to sixty” narrative?

Use your documentation to show a timeline of events and missed interventions. Point out consistent triggers, repeated patterns, and ignored warnings. Ask the school to describe what they will do differently next time to prevent escalation.

Why do schools use this framing?

Because it protects them from accountability. Claiming surprise makes it easier to avoid admitting they were warned, failed to act, or allowed unsafe conditions to persist.

What’s the most important takeaway for parents?

There is no such thing as a child who goes from zero to sixty. There are only children whose pain and signals have been ignored until they cannot hold it in any longer—and the responsibility for that lies with the adults who should have protected them.