I have been reflecting on the public reaction to the Cowichan case findings, and the deeper I look, the more I notice similar patterns emerging across conversations about reconciliation and disability justice in public schools: the tendency to get stuck in the T part of “Truth and Reconciliation” and to only have the T be genuine tea, when systems are compelled to spill.

A mirror of national tension

The Cowichan ruling reveals a convergence of fear, defensiveness, and inherited narratives about entitlement, because the moment truth demands structural movement the broader public responds with a kind of collective flinch, a gesture shaped by colonial memory and contemporary anxiety, and this pattern becomes visible across both land title conversations and the ways schools respond to disabled children whose needs illuminate institutional design flaws that will require major financial contributions to address. Everything feels manageable until someone raises the question of taxes or offers an unvarnished truth at a PAC meeting. Citizens collectively would prefer to pay lower taxes and have PAC meetings be fun discussions of pizza parties, unhampered by negative nancy’s, talking about systemic discrimination.

Land title panic and the economy of power

The reactions around land ownership after the Cowichan decision create an atmosphere of accelerated fear, because people who benefit from the existing landscape treat any shift toward Indigenous sovereignty as destabilising, and the rhetoric that surfaces in these moments circulates through familiar channels: warnings about loss, spirals of misinformation, and general catastrophising, such as:

- Fear that property systems will transform overnight.

- Rumours that merge speculation, prejudice, and financial panic.

- Assumptions that Indigenous leadership signals instability.

- Attempts to anchor the conversation in personal victimhood.

This emotional choreography belongs to a larger affective economy where truth enters the public sphere with some clarity while reconciliation advances only when it aligns with institutional comfort.

The intersection with public education’s colonial structure

Residential schools and public education belong to a single institutional lineage that continues to shape how authority operates in classrooms. This lineage reveals itself whenever disciplinary systems treat emotional pain as disorder and present inclusion as a symbolic gesture rather than an everyday commitment, producing patterns that echo through practices such as:

- collective punishment used as a tool for order

- shortened days presented as benevolent support

- learning modified through exclusion rather than accommodation

- behavioural programs organised around compliance

- crisis responses shaped by staffing shortages instead of care

These patterns echo older structures that treated children as subjects to be managed or projects of provincial improvement, rather than as community members to be supported.

-

The children were made to punish the children

In Canada’s residential schools, older children were instructed to punish the younger ones—to hit them, isolate them, report them for infractions defined by an institution that sought to erase who they were. The adults gave the orders. The children were conscripted to carry…

Collective punishment in residential schools and public schools today

My own response to collective punishment emerged from this historical awareness, because I carried the TRC’s findings in my mind long before a teacher applied group discipline to my daughter, and the collision between knowledge and lived experience produced an immediate sense of rupture, a recognition that the system still carries remnants of its colonial past within everyday practices.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission stated clearly that collective punishment served as a mechanism of control in residential schools, a tool used to enforce compliance through fear, shame, and group pressure, and this history reveals why the practice carries such a legacy of brutality that continues to cast a long and corrosive shadow today. The commission described how children were disciplined collectively for the actions of one, how entire dorms or classrooms were denied food, privileges, or safety, and how this method erased individuality and crushed autonomy.

Collective punishment functioned as a technique for suppressing emotion, shaping obedience, and maintaining institutional authority, and its legacy persists in the emotional memory of communities still living with the consequences of those systems.

When this practice appears in contemporary classrooms it signals a continuation of that lineage, because it treats the behaviour of one child as a burden to be redistributed across the group, positioning disabled or distressed children as sources of disruption rather than as individuals entitled to support.

The TRC called for the elimination of this practice because it causes harm, reinforces power imbalances, and reproduces the very dynamics that reconciliation seeks to dismantle, and its presence in modern public education affirms the urgency of structural transformation rather than incremental adjustment.

This history invites a wider view of how institutions across British Columbia respond to truth, because the same philosophy of control that shaped residential schools continues to guide the emotional reflexes of public systems today, creating an environment where harm is treated as an administrative detail and repair is framed as a distant aspiration, and this continuity reveals a shared foundation across conversations about land, schooling, and justice.

-

What would it really cost to fix the problem?

We talk so much about the cost of inclusion—as if it’s indulgent, optional, something that must be justified—but we rarely talk about the cost of exclusion. And those costs are everywhere: in emergency rooms, in overburdened case files, in classrooms where distress goes…

Reconciliation and disability justice intertwine

Reconciliation and disability justice both reveal how public systems absorb truth only when it arrives without fiscal consequence, and both expose how scarcity logic shapes institutional design long before any individual enters a classroom or a courtroom.

The public tends to treat systemic harm as a series of isolated unfortunate events rather than as evidence of structural design, a habit shaped by a preference for low taxes, minimal disruption, and a comforting belief that schools operate equitably. Exclusion is framed as an occasional sadness rather than a structural crisis, where equity is imagined as the norm rather than the exception, and where any call for significant investment is met with anxiety about cost.

Both reconciliation and disability justice challenge this pattern directly, because both require institutions to confront their origins, accept the scale of repair required, and redesign their structures with honesty about the ways control, scarcity, and fear shape public systems.

- both movements seek conditions rooted in dignity

- both challenge inherited authority

- both illuminate inequities that resist superficial remedies

- both rely on community persistence rather than institutional momentum

This alignment creates a shared horizon, because the transformation of our education system becomes a meaningful step toward reconciliation, and disability justice gains durability when it recognises the historical and cultural context that continues to shape exclusion.

Settler mentality

The conversation that erupted around the Cowichan findings has become a volatile spectacle. If I hear one more person proselytising about waves of homeowners losing mortgage renewals in Richmond I will barf. The rhetoric now feels like MAGA‑style panic dressed in West Coast politeness, a theatre of fear that reveals far more about racial anxiety and selective civic memory than about the decision itself.

I hold real empathy for anyone facing the possibility of losing their home, yet I also believe that genuine reconciliation arises through structural repair rather than personal sacrifice, because returning land, honouring rights, and investing in Indigenous sovereignty does not require individual families to lose the foundations of their lives.

Reconciliation becomes possible through collective mechanisms—government action, financial frameworks, and resource redistribution at the scale of the state—because the burden of repair belongs to institutions that accumulated advantage, not to households navigating mortgages, children, and daily life.

People are actually calling Cowichan selfish on social media, and the absurdity of that accusation reveals something essential about this moment, because the only people being asked to carry the emotional weight of reconciliation are the ones who already carry the burden of history, while the loudest critics frame any movement toward justice as greed, betrayal, or opportunism. This language exposes a deep discomfort with Indigenous authority and a persistent refusal to examine the systems that created inequity in the first place, and the public fury says far more about racial anxiety and inherited entitlement than it ever could about Cowichan’s actions.

Bad math and politics

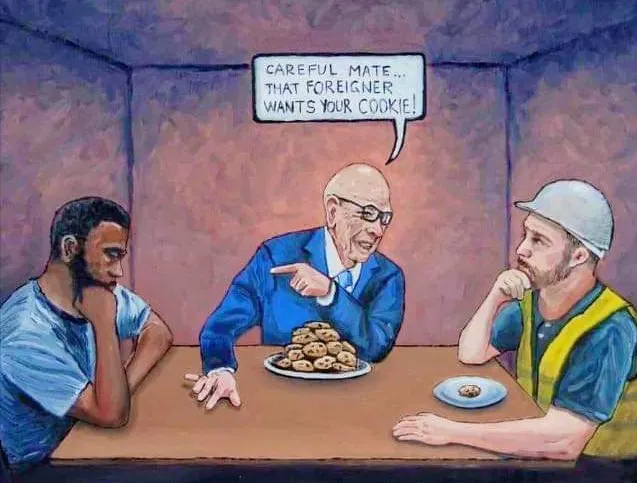

This reaction embodies the bad math that governs so much political discourse in British Columbia, a kind of public arithmetic where people panic about losing a single cookie while ignoring the person sitting beside them with an entire tray, because the fear has been engineered to focus downward or sideways rather than upward, encouraging citizens to distrust Indigenous nations, immigrants, disabled children, or families requesting support, instead of examining the systems that hoard resources and deflect responsibility.

This bad math thrives because it performs three functions at once:

- It reframes structural inequity as personal threat.

- It diverts attention away from concentrated wealth and underfunded public systems.

- It convinces people that justice is expensive while injustice is free.

This arithmetic circulates through conversations about land titles, where people fixate on hypothetical losses rather than on the documented history of dispossession, and it circulates through school politics, where families fear that supporting disabled children will drain resources from their own, even though the real crisis arises from decades of political choices that deliberately starved public education.

The bad math also produces deeply distorted emotional responses:

- People treat the recognition of Indigenous land rights as catastrophic, even when the legal frameworks are clear and bounded.

- People treat the need for educational assistants, resource teachers, and inclusive staffing as luxuries rather than as the baseline for a functioning system. The economy is bad! Times are hard. Blah blah blah!

- People treat equity as a burden rather than a responsibility, because scarcity has become a cultural script.

This script encourages a habitual miscalculation: the belief that justice will cost too much, that equality will destabilise the system, that repair is fiscally irresponsible, and that the safest path is the familiar one—even when the familiar one produces predictable harm.

The cartoon with the cookies captures this arithmetic perfectly: a person with a full plate warns another person with a single cookie to fear the neighbour with none, and the absurdity becomes the entire point, because the panic depends on distraction, misdirection, and the emotional convenience of blaming the wrong people. This is the political economy of exclusion in visual form, and the public response to the Cowichan ruling demonstrates just how effectively that economy continues to operate.

-

Counting crisis: data, distrust, and the false choice between safety and inclusion

Across British Columbia, the launch of Surrey DPAC’s Room Clear Tracker has ignited a storm of debate among parents, educators, and disability advocates. Some view it as a necessary step toward transparency; others fear it will reinforce stigma or justify segregation. Beneath the surface of this argument runs a deeper…

A few hoarders ruining life for the rest of us

Hoarding sits at the centre of these crises, because abundance remains concentrated in the hands of institutions, governments, and private actors who prefer to guard resources rather than release them into public systems that would transform collective life, and this preference shapes everything from land-title panic to exclusion in schools.

We could choose a different architecture, one where wealth, revenue, and political will flow toward equity with the same intensity that they currently flow toward preservation, and this choice would dissolve many of the harms we now treat as inevitable.

The capacity already exists for fully funded inclusive education, for meaningful restitution, for community-centred housing, and for stable supports that honour every child’s dignity. The barrier is the cultural commitment to scarcity, a worldview that treats redistribution as threat rather than as liberation.

The moment we shift from guarding to sharing, from fear to responsibility, the entire landscape changes, and the crises that feel overwhelming become solvable through collective design rather than individual sacrifice.

Every child benefits from a truly inclusive education, because inclusion strengthens cognitive, social, and emotional development for all learners, and a system designed for the margins enriches the centre with a depth of humanity and possibility that standardised models never achieve. Our country gains strength through genuine reconciliation, because communities flourish when their histories are honoured, their rights upheld, and their futures supported through structural investment rather than symbolic language.

A future shaped by clarity and structural courage

It all leaves me uneasy about the coming report from the Ombudsperson, because the public appetite for equity usually evaporates the moment someone whispers about taxes, and the entire conversation shifts from structural harm to personal inconvenience, as if fairness should arrive without a price tag. This moment offers an opportunity for public education to become a site where structural courage takes root, where reconciliation becomes more than ceremony, and where children experience classrooms shaped by autonomy, belonging, and collective responsibility, affirming that justice becomes real when systems choose transformation over comfort.